When the dismissal bell rang at Challis Elementary School on the afternoon of Monday, October 11, 1993, 9-year-old Stephanie Crane and some of her classmates walked down the street to Challis Lanes, where they participated in a weekly bowling league. Her mother, Sandi Crane, met her there around 4:00 pm and gave her money to buy a snack; Stephanie promised she would go straight home once she was done bowling. She and her friends spent the next hour or so bowling a few games and ordering food from the snack bar. By 4:45 pm, all of the children had finished bowling and started to go their separate ways.

The mother of one of Stephanie’s classmates saw her walking through the parking lot and asked if she needed a ride, but Stephanie told her she was fine. The 9-year-old was used to walking; her home was just 500 yards away from the bowling alley. She had to cross a small creek to get there, and when her friend’s mother last saw her, Stephanie was headed towards the small footbridge that led over Garden Creek.

Stephanie’s best friend, Brandi Bennetts, had been picked up at the bowling alley by her mother. As they pulled out of the parking lot, they noticed Stephanie waiting to cross Highway 93. Since this was in the opposite direction of her home, Brandi’s mom stopped the car and asked if Stephanie needed a ride somewhere. Stephanie told her that she was just running back to the elementary school because she had left her backpack on the soccer field; she declined the invitation of a ride, assuring Brandi and her mother that she was just going to retrieve her bag and then walk straight home.

Although Challis, Idaho, was the largest city in Custer County, it was tiny by most standards. Home to around 800 people, it was the kind of place where none of the residents ever bothered to lock their doors. Violent crime was almost non-existent; for children, it was a kind of utopia where they were allowed to roam around freely as long as they were home in time for dinner. All of this would change on the day Stephanie left the bowling alley to get her backpack, because at some point during her short walk, she vanished and was never seen again.

Sandi started to get concerned about her oldest daughter when she wasn’t home by 5:00 pm. She called the bowling alley but was told that Stephanie had already left and should have been home by then. Since Stephanie’s grandparents, Earl and Hazel Crane, lived right next door, Sandi thought her daughter might have stopped by their house. She called Hazel at 5:15 pm, but Hazel hadn’t seen the little girl. Since it was unlike Stephanie to come home late, Sandi and Hazel were worried enough that they immediately decided to drive around and look for her.

The sun started to set as they slowly drove up and down the streets of Challis, and panic started to set in. Stephanie was terrified of the dark — she could only fall asleep if she left her bedroom lights on — and Sandi knew that there was no way they were going to find her playing outside. Thinking that she might have gone to a friend’s house, the two women returned home and started calling all of the little girl’s friends and classmates. None of them had seen her since they left the bowling alley.

By 8:00 pm, Sandi had called everyone she knew but still had no idea where Stephanie was. Fearing the worst, she made the short drive to the Custer County Sheriff’s Office and told a deputy that she couldn’t find her daughter. It wasn’t the sort of report they were used to taking; they had answered only two calls for service that day, one regarding a traffic accident and the other involving an injured deer. Children simply didn’t go missing in Challis.

Law enforcement officials initially feared that Stephanie might have had some kind of accident. Deputies were immediately dispatched to search the creek that ran behind the bowling alley to make sure she hadn’t fallen into it and somehow drowned. After ruling that out as a possibility — the creek was shallow and didn’t have a very strong current — the search was expanded.

By 9:00 pm, most of the town was aware that Stephanie was missing. Dozens of residents helped deputies, firefighters, and members of the county’s search and rescue group comb through the area extending from the bowling alley to the elementary school. Tracking dogs seemed to pick up Stephanie’s scent near the bowling alley parking lot, but lost it after a short distance and were unable to determine which direction she had gone.

The search was temporarily halted shortly after midnight but started up again as soon as the sun rose. Still hoping that the little girl had somehow managed to spend the night undetected at a friend’s house, investigators held their breath and prayed that Stephanie would show up for school in the morning as if nothing had happened. Her desk remained empty.

The search kicked into high gear Tuesday morning. In addition to state and local law enforcement with search dogs and horses, a specialized search and rescue team was brought in from Blaine County. Firefighters and local volunteers also showed up in force, some using trucks and ATVs to cover ground more quickly. They combed through the rural area, checking sheds, garages, abandoned vehicles, and roadside ditches.

Most of the businesses in Challis either closed for the day or operated on skeleton crews as most of the workers joined in the search effort. Challis High School excused upperclassmen for the day so they could help as well. Everyone in town wanted to do everything possible to find Stephanie, but by the end of the day, there was still no sign of the missing child.

On Wednesday, more than 1,000 people participated in the search, which had expanded from Custer County into neighboring Lemhi County. Stephanie’s parents tried to remain optimistic, noting that Stephanie’s little sisters were too young to comprehend what was going on and they needed to remain strong for them.

The physical search was scaled back on Thursday. Officials were certain that they would have found Stephanie if she had simply been lost; the fact that they hadn’t found any clues to her whereabouts indicated to them that she had most likely been abducted. On Friday, investigators held a press conference and asked for anyone who had seen anything unusual on Monday afternoon to call them.

After the press conference, detectives received a number of tips about a suspicious yellow pickup truck with a red pinstripe that had been seen in the vicinity of the elementary school, but by the time they got the reports, the truck had already left the area. No one had thought to get the license plate number, making it nearly impossible to identify the owner of the truck.

The investigation was complicated by the fact that Stephanie had vanished during the middle of deer and elk hunting season. Hunters from all over the state passed through the small town during the season, using Highway 93 to get to and from remote hunting cabins. Detectives knew that Brandi had last seen Stephanie on the side of Highway 93; it was possible she had been grabbed by a transient who happened to see her standing alongside the road. If she had been pulled into a vehicle and immediately driven out of Challis, there was no telling where she might have ended up.

Friday was Challis High School’s homecoming, and though the festivities were still held the atmosphere was more somber than usual. The parade included banners reading “Bring Stephanie Home” and all of the floats included the color purple, Stephanie’s favorite.

By Saturday, there were only a few dozen people still actively involved in the physical search for Stephanie. They combed through a few remote areas that hadn’t been searched before but didn’t find anything; not willing to simply give up, some of the searchers started going back over areas that had already been combed through. No one wanted to give up on finding the missing 9-year-old.

Once it became clear that Stephanie had been abducted, Challis residents started raising money so they could offer a reward for her safe return. It took only a few days to raise $25,000, which an anonymous donor immediately offered to double. Volunteers created flyers with information about Stephanie and the $50,000 reward and began mailing them across the nation. With assistance from the Kevin Collins Foundation for Missing Children, they were able to send out more than 400,000 flyers within a week of the disappearance.

While volunteers did everything they could to bring national attention to Stephanie’s disappearance, detectives continued to work behind the scenes. They went to Challis Elementary School and interviewed all of Stephanie’s classmates; they were especially interested in what the children who had been at the bowling alley with her might have seen in the hour immediately before she went missing.

Chase McCoy, a classmate and friend, recalled that there had been a “creepy” man at the bowling alley who seemed to be paying close attention to the children as they bowled. He hadn’t thought too much of it at the time but in hindsight, he realized that this man might have had a sinister motive. Chase was able to describe what the man looked like to a sketch artist and a composite sketch was created. It was circulated throughout the state of Idaho but the man was never identified.

Hoping to reach a wider audience, volunteers enlisted the help of long-haul truckers, who agreed to distribute Stephanie’s missing person flyers at each stop along their cross-country routes. Some of the drivers even had large pictures of the missing girl painted on the back of the trucks along with a number to call if anyone had seen her.

The case was profiled on America’s Most Wanted, bringing much-needed national exposure to Stephanie’s disappearance, but the show failed to bring in any solid tips about what had happened to the little girl.

Two weeks into the search, officials admitted that they didn’t have much to go on. They had interviewed several men who resembled the composite sketch of the man seen at the bowling alley but were unable to connect any of them to the disappearance. Frustrated by the lack of leads, volunteers turned to psychics for advice about what to do next.

One psychic pointed out several areas in central Idaho where she believed the body of the 9-year-old would be found, prompting volunteers to conduct extensive searches of each area. Another psychic claimed Stephanie was about an hour away from Challis near Mackay, Idaho; she claimed the body would be found near a pond and some railroad tracks. Searchers located an area that seemed to match the psychic’s description — although the railroad tracks had been removed years earlier — but found nothing to indicate Stephanie had been there.

On October 28, the Custer County Sheriff’s Office issued a statewide alert for Stephanie’s great-uncle, Robert Paul Crane. They stressed to the public that he wasn’t considered a suspect in the case but was wanted for questioning as he had owned a yellow pickup truck at one time. His whereabouts, however, had been unknown since June 1989, when he was out on probation for a DUI offense. He was wanted for a probation violation and deputies were told to consider him armed and dangerous.

A week later, Robert was located by the FBI in Colorado. He was arrested for probation violation on November 4, but was able to provide a solid alibi for the time of his great-niece’s disappearance and was eliminated as a possible suspect.

There was little progress made on the case over the next 10 months. On September 27, 1994, Challis residents gathered to honor Stephanie on the eve of her 10th birthday. They offered prayers for her safe return and released purple balloons into the sky with messages of hope. Although they were trying to stay optimistic, it was clear that the case had gone cold.

Sandi and Ben never really recovered from the shock of losing their oldest daughter and their marriage fell apart. Ben, stoic by nature, tended to keep his feelings bottled up inside while Sandi was more emotional and needed to talk about the disappearance. The tension between them reached a breaking point in August 1995 and the couple made the difficult decision to divorce.

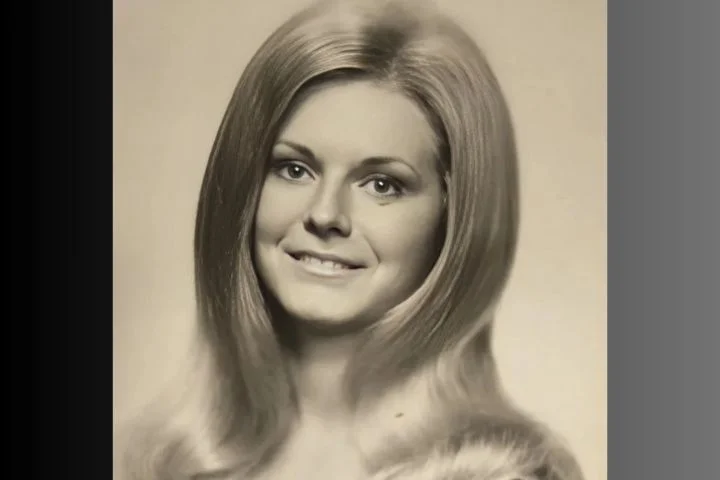

Sandi was plagued by health problems and died just two years later. Her official cause of d*eath was from blood clots in her lungs, but Hazel Crane believes her former daughter-in-law died of a broken heart. She was just 32 years old.

By April 2000, Stephanie’s case had long gone cold when authorities in Canyon County, Idaho, received a call that jumpstarted the investigation. An inmate in a Canyon County jail claimed that he had a female friend who knew the person responsible for Stephanie’s abduction. Detectives immediately reached out to the inmate’s friend, who agreed to come into the station for an interview.

The woman told investigators that in 1993 she had rented a room in Nampa, Idaho, from a man who she believed had kidnapped Stephanie. He was a drifter who rarely stayed in one location for very long, bouncing back and forth between towns in Oregon and Idaho. According to the woman, neighbors of the man claimed that they had heard the sounds of a young girl screaming and crying coming from his basement, an area of the house that he didn’t let anyone else enter.

Neighbors told the woman that they believed he had been holding someone captive but when she asked the man about it he shrugged it off, claiming that the cries they heard had come from his own daughter. According to him, he had to keep her locked up because she kept running away. The woman was unable to gain access to the basement, but she did rummage through the man’s belongings when he was out one day and was surprised to find several pairs of underwear that appeared to belong to a young girl.

At this point, the woman claimed she became so frightened of the man that she packed up her own children and left; the drifter also left the area around the same time. Neither the woman nor any of the neighbors ever bothered to call police to report their suspicions about the drifter.

Detectives looked into the background of the drifter and found that he had been arrested in Portland, Oregon in November 1992 on charges that he sexually abused his young daughter. Incredibly, though he was convicted of sexual abusing a minor, he served no jail time. He was released on probation, though he wasn’t allowed to have any contact with his daughter. Shortly after his conviction, he left Portland for Idaho.

Investigators located the man in May 2000 and asked him to come in for an interview. The man willingly came into the police station and even agreed to take a polygraph examination about Stephanie’s abduction, but he became irate and non-cooperative once detectives informed him that he had failed the polygraph.

Convinced that the drifter was the man they had been looking for, investigators obtained a search warrant for his old residence in Nampa. In the basement, they found old mattresses, rope, strands of hair, and what appeared to be blood stains on the floor. They carefully collected samples of everything and sent them to the state crime lab for analysis, hoping that technicians would be able to find evidence linking the man to Stephanie.

Unfortunately, all the test results came back as inconclusive. The lab was unable to determine if the blood had come from a human, and the strands of hair had no follicles attached and were useless for DNA testing. With no conclusive evidence that Stephanie had been in the man’s residence, detectives were forced to let him go without charges.

Not willing to give up on what had been their only real lead in years, investigators created a photo lineup that included the drifter’s picture and showed it to employees of the Challis bowling alley who had been working the night Stephanie had vanished. They hoped someone might recognize the drifter as the creepy man who had been watching the children as they bowled, but they ran into another dead end. One employee picked the drifter’s photo but said she couldn’t be certain that was the man she had seen.

Two years later, another potential suspect was brought to the attention of Custer County investigators. On June 5, 2002, Keith Glenn Hescock, a 42-year-old man who was suspected in the 2001 disappearance of a 20-year-old woman, kidnapped a 14-year-old girl from her home in Idaho Falls. He took her to his house, where he chained her to his bed and raped her. He told her that he had killed before and intended to do the same to her, but he had to go to work first.

After he left, the terrified teenager managed to free her hands and then used a fire extinguisher to break the chains that were holding her so that she could escape. She was able to lead police to Keith’s home and a SWAT team was dispatched there to arrest him when he returned. Keith, however, wasn’t willing to go down without a fight. He seemed to realize something was up as soon as he arrived; he then took off in his truck, leading police on a high-speed chase for more than 40 miles.

The chase ended when Keith hit a dead end and was unable to drive any further. Rather than surrender, he started shooting at the deputies. After killing a police dog and wounding a deputy, Keith shot himself in the head. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

Investigators working on Stephanie’s case had interviewed Keith in 1997 after he was cited for illegal poaching in the Challis area. They learned that he had been hunting in the same area around the time that Stephanie had vanished and had considered him a person of interest at the time but had no evidence to connect him to her abduction.

After they heard that Keith had abducted and raped a 14-year-old, detectives took another look at the possibility that he might have killed Stephanie. Unfortunately, his suicide meant that they couldn’t question him about the case; although they went through truckloads of potential evidence that was removed from his residence, they found nothing to link him to Stephanie.

Sadly, on October 11, 2012, exactly 19 years after Stephanie vanished, her father Ben died after suffering a massive heart attack. He had never fully gotten over the loss of his oldest daughter and was just 48 years old when he died.

While detectives believe that Stephanie was most likely killed shortly after her abduction in 1993, she is still considered a missing person and they have never stopped looking for her. In June 2016, detectives focused their attention on the drifter again. Although they have never released his name to the media, they have interviewed him several times and many are convinced that he is the person responsible for Stephanie’s disappearance. As of July 2022, he remains a person of interest.

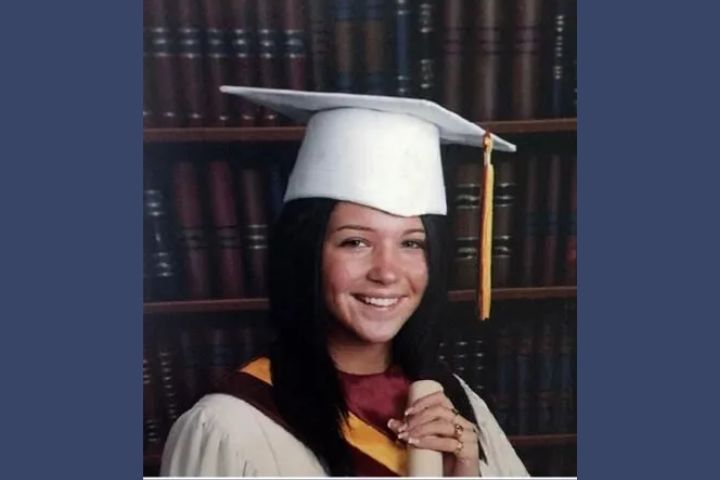

Stephanie Crane was just 9 years old when she was abducted in 1993. She was a tomboy who loved going on fishing and hunting trips with her father, and as the first grandchild of the family, she had a very special relationship with her grandmother, Hazel. She was friendly, outgoing, and fun to be around; classmates recall that she was the kind of person who liked everyone and made friends easily. At the time of her disappearance, Stephanie was 4 feet 2 inches tall and weighed 75 pounds. She has blue eyes and thick, curly, brown hair. She was last seen wearing a maroon and white hoodie with “GIMMIE” on the front in white letters, maroon sweatpants, and maroon and white sneakers.

Officials believe that there are people out there who know exactly what happened to Stephanie and they hope that someone will finally come forward with the evidence they need to identify her abductor. The person responsible for the crime has most likely mentioned it to people over the years; it’s also possible that the people who he confided in didn’t believe him at the time. If you have any information about Stephanie’s case, no matter how insignificant, please call the Custer County Sheriff’s Office at 208–879–2232.