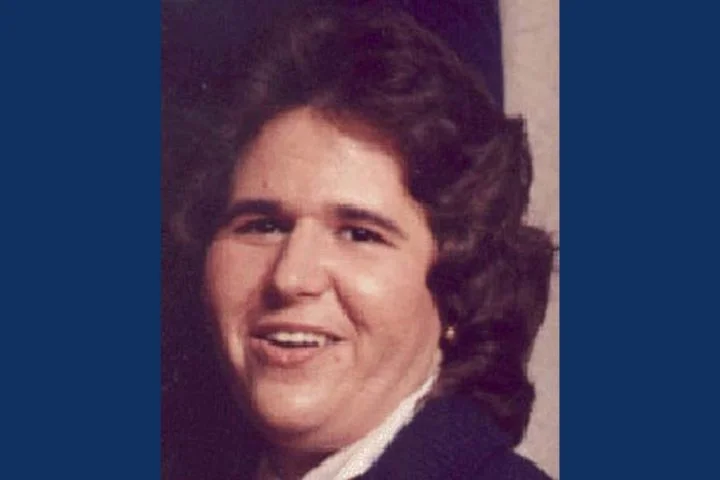

Barbara Newhall Follet was born on March 4, 1914, in Hanover, New Hampshire. Helen Thomas Follett, her mother, wrote children’s books. Her father Roy Wilson Follett was an editor, literary critic, and English teacher. He’d won the 1909 Oliver Wendell Holmes Scholarship at Harvard. Roy then proceeded to teach English at Dartmouth College and Brown University. Posthumously, he is known for Follett’s Modern American Usage, his only book and a guide to contemporary American English.

Barbara’s parents decided it would be best for their daughter if she were homeschooled so that she could focus better on her interests —her biggest fascination being nature, which would become an important component in her writing.

According to her mother, by age three, Barbara had already developed a passion for books.

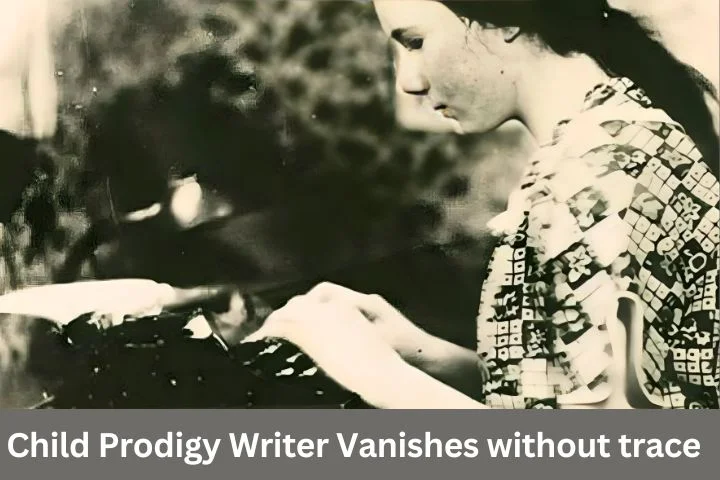

The family relocated to New Haven, Connecticut, where Roy Wilson worked at Yale University Press. While in his workroom at home, clicking on his typewriter, 4-year-old Barbara became interested in the machine. Soon, she had her own portable typewriter and workroom.

She wrote letters to friends and family, short stories, poems, and even music. By age 6, Barbara had written a 4500-word story, “The Life of the Spinning-Wheel, the Rocking Horse, and the Rabbit”.

The young girl was so creative that she even invented her own planet, Farksolia, with its own language, Farksoo. She pretended to be friends with Beethoven, the Straus brothers, and Wagner, claiming they would go skating with her sometimes. As for real friends, she had few, preferring the company of adults.

It was customary for Barbara to give presents to others on her own birthday, and her 9th anniversary was no exception. Barbara gave her mother a book she’d written about a child who runs away from home to go live with animals in nature: “The Adventure of Eepersip”.

Her father though the novel had potential and proposed that she review it during the summer. However, Barbara was left distraught when she lost the manuscript after a fire destroyed their house.

Barbara continued to write other stories but couldn’t let go of Eepersip. The next two years were spent rewriting it and when she finished it, her father thought it was deserving of being published. He showed the novel to his boss, Alfred A. Knopf, and the publisher loved it.

The book was renamed “A House Without Windows, and Eepersip’s Life There”, and published in January of 1927.

Barbara, at just 12-years-old, was now a published author.

The New York Times, The Saturday Review, and H.L. Mencken wrote about the novel and had nothing but admiration for it.

Despite the novel being critically acclaimed, there was one person who wasn’t so sure about all the praise. Anne Caroll Moore, from the New York Herald Tribune and a strong advocate for children’s literature, did not think that publishing the book was a good idea. While she did praise the story itself, she claimed that young Barbara should have a normal childhood and not be subjected to fame.

Barbara, however, had no intentions on quitting storytelling.

Shortly after, she embarked on a ten-day trip to Nova Scotia with a family friend, George Bryan, on a lumber schooner, the Frederick H. She agreed to go as long as she was allowed to do chores.

Upon her return, she completed her second book: a part memoir, part fiction about her voyage.

Once again, Knoph was impressed and published “The Voyage of Norman D” in 1928.

The 14-year-old was once again the writer of a critically acclaimed book.

While Barbara was focused on her second novel, “The Voyages of Norman D”, her home life had been deteriorating.

Her father had been spending an increasing amount of his time in New York working as an editor for Knopf. Barbara was left distraught when her father, with whom she was very close to, informed the family that he was leaving.

He’d met Margaret Whipple, a younger woman, and Knopf’s secretary.

Just days before her fourteenth birthday, she begged her father to stay. He didn’t.

As a result, Barbara and her mother Helen were left with financial troubles. With nothing holding them down, the two decided to go on a sea trip. They brought only essentials — one suitcase and two bags, each with their typewriter.

The two traveled to Barbados, then went along the Panama Canal to Tahiti, Fiji, the Toga Islands, and Samoa, reaching Honolulu in May 1929. They then boarded the Vigilant where their sailing trip came to an end in Hoaquim, Washington.

Barbara and Helen, now in Pasadena staying with friends, hadn’t been getting along too well. The mother and daughter agreed that they should spend some time apart. Helen returned to Honolulu and wrote books about their voyages. Barbara stayed with her new guardian, Dr. Ture Schultz, in Pasadena. She briefly attended Pasadena Junior College until she ran away to San Francisco where she planned to live as a typist.

Her escape didn’t go as planned, however, and she was reported as a runaway. When police knocked on her hotel room door in San Francisco, she tried to jump out the window. Authorities managed to arrest her and she spent the next few days detained, as she did not want to be returned to her guardian.

The story ran nationwide, and she told the media that she hated Los Angeles and called her life in Pasadena poisonous.

It’s unclear what decision was made during this time, but Barbara and her mother soon boarded the SS Marsdak and went from San Diego to Baltimore. Together, Barbara and Helen finished “Magic Portholes” while in Washington DC and had it published in 1932.

The mother and daughter then lived in an apartment in New York where Barbara focused on her third novel, “Lost Island”. Their financial struggles were worsening and Barbara, aged 16, was forced to have various jobs such as writing synapses for books for Fox Films and typing for hire.

In the summer of 1931, Barbara was living in a cabin in Vermont. There, she met a group of Dartmouth College students, including Nickerson Rogers. The two immediately bonded, as they both shared an intense interest in nature.

The next year, when Rogers and Barbara were dating, the two spent several months in the New England Mountains, exploring between Katahdin and Vermont by foot and canoe.

Their next stop was Europe; the two sailed there and lived like gypsies for a year. They also called each other husband and wife, despite not being officially married. While in Europe, they explored Spain, hiked in the Alpes and the Black Forest.

In 1933, the couple settled down in Boston, where Rogers’ home was, and they married. During the next couple of years, they moved within Boston and then relocated to Brookline, Massassuchets. Barbara worked as a secretary, while Rogers was an engineer.

Despite her marriage, relocating various times, and having a regular job, Barbara continued to write — mostly short stories about their travels.

Sadly, she couldn’t find anyone willing to publish “Long Island”, which she had completed upon her return from Europe.

What was at first a happy marriage, became depressing to Barbara. Rogers was increasingly busy with his work and their travels were almost non-existent.

In 1936, Barbara did find a new passion, interpretive dancing. She joined Mary Starks’ Dance Workshop Group. Moreover, she reconnected with her father, who now had another daughter, Jane, with Margaret Whipple and lived in Bradford, Vermont.

In 1939, Barbara and her friend Lee, from the dance workshop, took a road trip together. The went to Bennington School of Dance, at Mills College, in Oakland, where Barbara enrolled in a workshop.

She then stopped to visit a friend in Pasadena. While there, she received a devastating letter from her husband Rogers who was back in Brookline. He wanted a divorce. She immediately traveled back home, only to find out that Rogers was interested in someone else — she didn’t want to know who it was and never found out.

She convinced Rogers to give their relationship another try for a month. She seemed confident it was working, although it didn’t change his mind. Barbara became depressed and blamed herself for his departure.

On the evening of December 7, 1939, after having an argument with Rogers, Barbara left their apartment with $30 (over $500 nowadays) and a notebook.

The 25-year-old was never seen again.

Oddly, Rogers waited two weeks before reporting his wife missing to the police, claiming he was waiting for her to come back. Authorities checked to see if her body was at the Boston morgue, but there were no matches.

Only four months after did Rogers request a missing persons bulletin. Despite Barbara’s fame, her disappearance went unnoticed by the media. Largely because the bulletin was issued with her married name and not her own.

Her mother only discovered that her daughter went missing in the mid-40s. When she found out that Rogers didn’t do much to find her, she said,

“All of this silence on your part looks as if you had something to hide concerning Barbara’s disappearance … You cannot believe that I shall sit idle during my last few years and not make whatever effort I can to find out whether Bar is alive or de*ad, whether, perhaps, she is in some institution suffering from amnesia or nervous breakdown.”

She tried to get the Brookline police to investigate the case further, but to no avail.

When Helen co-authored an academic study on her daughter in 1966, the media finally took notice that the author had been missing all those years.

Roy Wilson wrote an anonymous essay to The Atlantic, “To a Daughter, One Year Lost”, where he expressed his guilt and amazement towards his missing daughter.

Barbara’s half-nephew Stephan Cooke believes she started a new life. He doesn’t believe that someone like her and at such a young age would commit suicide.

Interestingly, Jane, Barbara’s half-sister, believes it is a possibility that Barbara went to the White Mountains and froze to de*ath by choice.