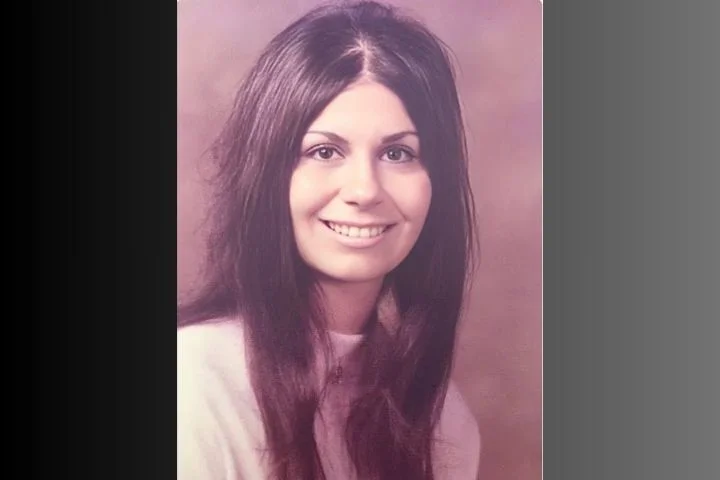

Judy Martins was excited about her plans for the upcoming Memorial Day weekend in 1978. The 22-year-old, who was a junior at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, was going to be spending the weekend with two of her friends in New York. On Tuesday, May 23, 1978, Judy left her dorm room in Engleman Hall and visited with some friends who lived in Dunbar Hall. After visiting with her friends for a couple of hours, Judy left their dorm room around 2:30 am Wednesday to make the five-minute walk back to Engleman Hall. She never made it back to her room and she was never seen again.

Judy was a resident assistant for her dormitory; one of the perks that came with the position was a single room. Because of this, Judy had no roommate to raise the alarm when she didn’t make it back to her dorm room and her disappearance initially went unnoticed. One of her friends reported her missing to campus police Thursday night, and officials didn’t call Judy’s parents until Friday afternoon.

Kent State police initially believed that Judy had gone off voluntarily and would likely return once the holiday weekend was over. Although they told Judy’s family that they had searched the campus for the missing student, the extent of their search was unknown. Most of Judy’s classmates had already left for the weekend and weren’t around to be questioned.

Friends who had seen Judy in the hours leading up to her disappearance told police that she had been in a good mood when she left Dunbar Hall and had planned to go right back to her room. The friends had been celebrating the fact that the spring quarter was almost over, and Judy had pranked her friends by dressing up as a prostitute that night. She had still been wearing a curly red wig when she left to walk back to her room.

Judy was the oldest daughter of Arthur and Dolores Martins; she had a younger sister and a younger brother. She was a 1973 graduate of Avon Lake High School, and she enrolled at Ohio University the fall after her graduation. She spent two years there before deciding to take some time off from school; after moving back in with her parents for a couple of years, she decided to go to Kent State.

Judy had always been a good student and was serious about her education. She was an art major at Kent State and was minoring in women’s studies; she was hoping to one day become a therapist and hadn’t ruled out the idea of going to graduate school. She enjoyed helping people and was a volunteer counselor at Kent State’s Pregnancy Information Center.

A friendly and outgoing young woman, Judy made friends easily and was popular on campus. She loved to have fun and joke around with her friends; she was described as being the life of the party and could light up a room with her smile.

Although campus police insisted that Judy would return when she was ready, her family was adamant that Judy wasn’t the type of person who would go anywhere for an extended amount of time without letting them know where she was going to be. Judy was especially close with her younger sister, Nancy; the two spoke on the phone frequently and Nancy was certain Judy would have called her if she were able.

From the beginning, the Kent police force seemed to want to downplay Judy’s disappearance; her family believes the university was still trying to overcome the public relations nightmare caused by the Kent State shootings in 1970 and didn’t want any negative press resulting from a missing student.

A week after Judy was last seen, officials with the Kent State University Police Department made a public appeal for information about Judy’s whereabouts. They noted that the missing woman was “reliable and dependable” and her family didn’t think she had vanished voluntarily. They said that they had contacted local police departments and listed Judy as missing with a nationwide police network, but they didn’t have any organized searches planned.

The following week, Kent State Police Chief Robert Malone said that detectives had reason to believe that Judy had gone to Mexico. According to Chief Malone, Judy had been spotted at a Kent garage sale on Memorial Day; she had spent about an hour looking through the various items for sale before purchasing some clothing and told several residents that she was planning to hitchhike to Mexico. The witnesses were shown photographs of Judy and told investigators that they were certain she was the woman they had seen.

Although investigators believed that the witnesses were credible, Chief Malone told reporters that they were still going to conduct an aerial search of the Kent State campus and surrounding area. In addition, the Kent State University Foundation was offering a $1,500 reward for information leading to Judy’s whereabouts.

Judy’s parents didn’t believe that she would have hitchhiked anywhere; she had no history of doing so and had her own car waiting for her at home. They believed it was most likely a case of mistaken identity and that the witnesses had actually seen someone else.

On June 5, 1978, the woman who had been seen at the garage sale was spotted again; this time she was getting a passport photograph taken in preparation for her trip to Mexico. Although she did resemble Judy, investigators spoke with her and were able to confirm she was not the missing woman. As Judy’s parents had feared, the witnesses had been mistaken and their daughter’s location remained a mystery.

Dolores was certain that her daughter hadn’t planned to disappear. “We never had any problems with Judy. We always had a good relationship.” All of Judy’s belongings had been left behind in her dorm room, including her clothing, books, cosmetics, and eyeglasses. “I know every item of clothing she had. Nothing was missing” Judy had been wearing her contacts when she went missing; she never wore them overnight and likely intended to take them out as soon as she got back to her room. She had problems with her eyesight due to a flattened cornea, and she never would have traveled anywhere without taking her glasses with her.

Kent State officials admitted that they had no idea what had happened to Judy. They had used a helicopter equipped with heat-seeking radar to search the campus and a large wooded area but hadn’t found any sign of Judy. All of Judy’s friends and acquaintances were interviewed, and four people — including a man Judy had been dating — took and passed polygraph examinations. None of them were able to offer any clues as to what had happened to her.

Kent State Detective Tim Brandon was assigned Judy’s case, but he told reporters that he didn’t have a lot to work with. “We are investigating minor leads, but nothing has turned out to be significant.” Her case failed to attract any meaningful media attention and as a result, detectives received few tips. Before the summer was over, the investigation had stalled and the case soon went cold.

In January 1980, Nan Abdo, a friend of the Martins family, announced that she was offering a $10,000 reward for information leading to Judy’s return. “My father left me a small inheritance, so I wanted to do something concrete to help find Judy. It’s a long shot, but maybe this will do the trick.”

Judy’s parents had considered hiring a private investigator to help locate their daughter, but they hadn’t been able to afford one. Dolores noted, “They are out of the reach of the average family.” They had been grateful when Nan decided to offer a reward for information and were hopeful that someone would finally come forward. “Somebody somewhere has to know something about where she is.”

Although investigators with the Kent State Police Department said they were still actively working the case, they hadn’t received any new tips in months. The lack of information had been hard on Judy’s family. Dolores noted, “We’ve had some bizarre rumors from time to time, but they have led nowhere.” One persistent rumor had been that Judy was working as a prostitute in Cleveland, Ohio. “We checked it out…it’s unfounded.”

Every week, Dolores would call investigators to see if there were any updates on Judy’s case. Unfortunately, detectives never had anything new to report. “Some days are hard to get through. I would prefer to think that she’s alive somewhere, but that’s hard to believe now. She was so family oriented…I know she would have tried to at least call us.”

Chief Malone admitted that the case had been a frustrating one for detectives. “To my knowledge, this is the only case we have had at Kent State of a missing person who could not be accounted for…we get a lot of missing person reports here, but there always seems to be an explanation.” Only Judy’s case remained unexplainable.

In February 1980, Kent State Deputy Chief John Peach said detectives were looking into the possibility that a man named William Posey might have been involved in Judy’s disappearance. Posey had been arrested and charged with the abduction and mu*rder of a woman in Illinois, and Kent detectives became interested in him when they learned that he had lived in Kent from June 1978 until September 1979. There was no evidence linking him to Judy, however, and he denied having anything to do with her disappearance.

In March, Deputy Chief Peach told reporters that he didn’t believe Posey had been responsible for Judy’s disappearance. “We have placed him in Columbus on May 11, 1978, but we can’t place him in Kent at all during May 1978.”

Later that year, Posey pleaded guilty to mur*der charges in Illinois, and in 1981 he was convicted of kidnapping a woman in Vermont. He was sentenced to life in prison; in 2008, after being diagnosed with a terminal illness, he admitted that he had killed his Vermont kidnapping victim and told police he had thrown her body over a guardrail along Interstate 89 outside of Burlington. Posey was never charged in connection with Judy’s case and always maintained that he had nothing to do with her disappearance.

Desperate to find their daughter, Arthur and Dolores decided to speak with a psychic. Although neither of them had ever believed in mediums before, they were willing to try anything. Dolores noted, “We brought this woman an article of Judy’s clothing, and she told us things about Judy, personal things about her that were never in any newspaper, things that only we could know.”

Unfortunately, the psychic didn’t have good news for the couple. She told them that their daughter had been abducted and mur*dered by a trio of men. “She said Judy’s body was ditched from an airplane flying at a low altitude. She said the body is in a heavily wooded, uninhabited island at least 50 miles northwest of Kent.”

Police admitted that there were islands in Lake Erie that fit the description provided by the psychic, and officials assured the Martins that they would conduct a search of some of the islands once the weather got warmer. The psychic seemed to think they would be successful; she told Judy’s parents, “The earth will give up Judy’s body in April or May.” By the end of May, it was clear that the psychic’s prediction about Judy’s recovery was wrong. She remained missing, and her case soon went cold once more.

Sadly, Judy’s case appeared to be forgotten over the next several decades; there were no articles or news reports about the case and it was unclear if any detectives were still searching for her. Incredibly, in 2000, Kent University got rid of all its files concerning Judy’s disappearance; officials apparently didn’t see any need to keep the case active despite the fact that Judy had never been found. They later told Judy’s family that the files had been properly disposed of in accordance with the university’s records retention policy.

Deputy Chief Peach admitted that many of the records had been thrown away, but some had been shared with the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation. “It was never classified as a crime, and that was before the guidelines for missing persons were established, well before we were able to keep electronic versions of records.” He said that he still wondered what had happened to Judy so many years earlier. “It’s just a bizarre case. To this day, it’s too bizarre for me to even think what happened. We don’t know it’s a crime, but it’s too unusual to think that a crime wasn’t involved.”

In the years since Judy went missing, both of her parents have died. Her sister, Nancy, noted that Judy’s disappearance had deeply affected her mother and father. “Their lives were cut short by this.” Arnold was just 57 when he died; Dolores was 71.

Nancy and her brother, Steve, submitted samples of the DNA to the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation so they could build a profile for Judy and check for matches with unidentified bodies across the United States. Both siblings had come to terms with the fact that Judy is almost certainly dead, but they still wanted to be able to give her a proper burial. Steve noted, “The not knowing is very difficult, and it would be much better to know what happened, no matter how tragic.”

For Nancy, one of the greatest tragedies is the fact that the Kent University Police Department didn’t seem to care that her sister was missing. “That Kent State destroyed its files on Judy’s disappearance is probably the most painful part.” In May 2023, she noted, “We’re at the point where we don’t care about prosecution or anything else. All we want to know is where she is and what happened to her.”

Judy Martins was just 22 years old when she vanished from Kent, Ohio in May 1978. Detectives initially believed that Judy had voluntarily gone missing, but her family was certain that she had been a victim of foul play. By the time investigators realized that Judy wasn’t a runaway, the case had already gone cold. Judy has hazel eyes and black hair, and at the time of her disappearance, she was 5 feet 4 inches tall and weighed 120 pounds. Judy was last seen wearing denim gaucho-style pants, a yellow and brown blouse, brown boots, and a light-colored trench coat. She was also wearing a curly red wig and carrying a large white purse. If you have any information about Judy, please contact the Ohio Attorney General’s Office at 330–672–3070 or the U.S. Marshals Tip Line at 866–492–6833. You may remain anonymous.