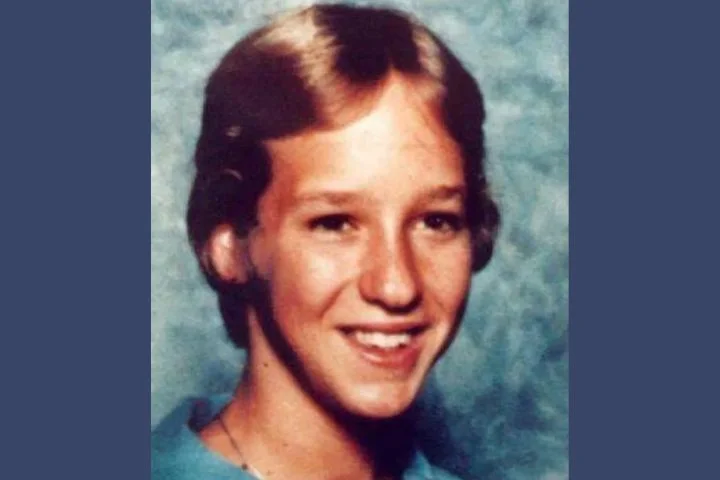

March 18 – At 18 months old, Brandenn E. Bremmer began to read, his mother says. At 3, he played the piano, finished the schoolwork of an average first grader and announced that he did not care to go back to preschool. At 10, he graduated from high school, his precocious accomplishments drawing the spotlight of the national news media.

This week, at 14, Brandenn die*d. Sheriff’s deputies in his rural Nebraska hometown near the Colorado border said the gunshot wound to his head was apparently a sui*cide.

Brandenn’s life and enormous promise, like that of a handful of other child prodigies in the United States, drew the awe of adults who met him or heard of him or heard some bars of the music that he composed.

His de*ath left them shaken, saying they wondered about the struggle of any life with a foot in each of the two worlds that Brandenn inhabited — a child, but because of his brilliance, not really a child at all.

“He really to me seemed no different than any other normal kid growing up, but yet you still knew that he was different,” said Steven Tucker, a farmer who lives not far from the Bremmer family in Venango, Neb.

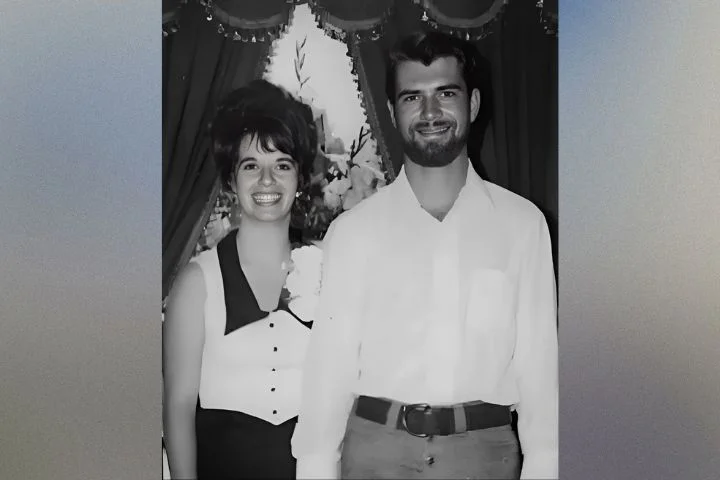

Brandenn’s mother, Patti, who found him shot when she and her husband, Martin, returned home from grocery shopping on Tuesday evening, said that Brandenn, who started college at 11, had been different, to be sure. But he had never been depressed, lonely or pressured to achieve.

“So many people will want to say he was maladjusted or not socially adjusted, but that’s just not so at all,” Ms. Bremmer said in a telephone interview. “It makes me mad. People need to understand. These kids are so much more intelligent than they are.

“We never pushed Brandenn. He made his own choices. He taught himself to read. If anything, we tried to hold him back a little.”

Brandenn left no note, no goodbye. He had seemed cheery earlier in the day, before she left for the store, Ms. Bremmer said. She said he was busy with preparations to become an anesthesiologist, with his friends and with plans for the imminent release of a second CD of music he had composed, in the style, somewhat, of Yanni.

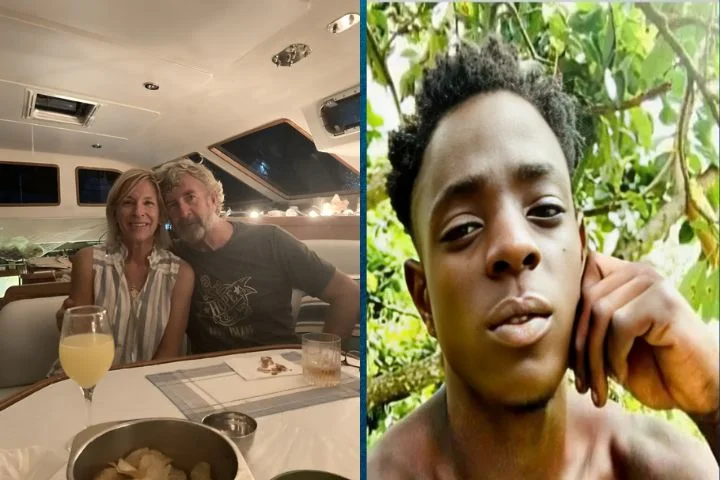

Ms. Bremmer, who writes mystery books and whose family raises and trains dogs, said she took comfort in her sense that Brandenn must have chosen his course because his organs — heart, liver and kidneys — were needed by ailing people.

“He was so in touch with the spiritual world,” Ms. Bremmer said. “He was always that way, and we believe he could hear people’s needs. He left to save those people.”

The vital organs were donated the night he d*ied, as he had long made clear was his wish, she said.

Ms. Bremmer said that she and Mr. Bremmer had always known that Brandenn, who had two much older sisters, was unusual. The day he was born, doctors struggled to find a pulse, she said.

“Things were different right from then,” she recalled. “It’s almost like my baby d*ied, and an angel took his place.”

Still, many who knew him said he seemed quite ordinary, despite the circumstances of his life that might have led, or even been expected to lead, to eccentricity or worse.

He could act like an adult one moment and like a child the next, said Jim Schiefelbein, former principal of University of Nebraska-Lincoln Independent Study High School, which Brandenn started attending at age 6 and finished four years later. Mr. Schiefelbein recalled how at his graduation, Brandenn, then 10, offered a few words of thanks, spoke to the news media and promptly began running around the room with other children at the ceremony.

At Colorado State in Fort Collins, where he took college courses before transferring to a community college in Nebraska closer to home, two professors who knew him described him as reserved, but not withdrawn — clearly set apart in a sea of 18-to-22-year-olds, but not entirely isolated.

Brian Jones, a physics instructor and the director of an outreach project, Little Shop of Physics, which works with junior high school pupils, met Brandenn after a music professor told him about the piano prodigy who was coming to the campus.

Brandenn sat in on physics classes, surrounded by college students, but then participated, as well, in helping younger children who were closer to his age. He was able to play and have fun, Mr. Jones said, but then return the next day and work on his research projects alongside people 10 years his senior.

“I never would have worried about him at all,” Mr. Jones said.

Brandenn, his mother said, “had no chronological age.”

“He was comfortable with a baby,” she said. “And he was comfortable with someone 90 years old.”