Tracey Bradley left her Chicago, Illinois apartment around 6:00 am on Friday, July 6, 2001, to go to work. The single mother left her two young daughters, 3-year-old Diamond and 10-year-old Tionda, alone in the apartment and told them to make sure they didn’t let anyone into the apartment. She expected them to be there waiting for her when she returned from work around 12:30 pm. When Tracey got home, however, there was no sign of the girls, only a handwritten note propped on the back of the couch. The note indicated that the sisters would be at the playground at Doolittle Elementary School or the Lake Meadows Shopping Center across the street from the school.

Doolittle Elementary School, where Tionda had been enrolled in summer classes, was just two blocks from the family’s home in the Lake Grove Village Apartment complex. Tionda had taken her sister to the playground there before, but she would normally call her mother’s cell phone to get permission before doing so. She had never left a note before, and Tracey felt uneasy about the situation. She spent the next several hours searching the neighborhood for any sign of her two daughters, hoping someone might have seen them. Neighbor Fred Ramsey said that Tionda had knocked on his door around 10:00 am to see if his daughter could come out and play, but he sent Tionda away as his daughter was still in bed.

By 6:00 pm, the two sisters were still missing. Fearing that something had happened to them, Tracey called the Chicago Police Department and reported Diamond and Tionda missing. Dozens of officers immediately started scouring the South Side neighborhood for any sign of the two girls. They found no clues to their whereabouts.

The search intensified on Saturday. Officers went door-to-door, distributing missing person flyers and looking for anyone who might have seen the children after they left their apartment. A helicopter scanned the area from above while a marine unit searched Lake Michigan. Chicago Police Lt. Robert Biebel told reporters that investigators had no idea what had happened to the girls, but they hadn’t found any evidence pointing to foul play. “Anything could have happened. We’re just hoping they’re in a neighbor’s house somewhere.”

By Sunday, more than 100 officers as well as scores of volunteers were involved in the search effort. There had been no reported sightings of the sisters, and police were growing increasingly worried for their safety. Police spokesman Pat Camden told reporters, “This is, in police department terminology, two tender-age children. It really raises the concern.”

Officers used police dogs to search through parked cars and along railroad tracks. Eventually, the search was expanded to include nearby wooded areas and abandoned buildings. Several helicopters continued to search from the air, and marine units used sonar to search along the lakefront.

Detectives interviewed each child’s father as well as relatives and friends of the family. None of them had any idea where the sisters could be. Shelia Smith, the sisters’ great-aunt, told reporters that the family believed that foul play was involved in the girls’ disappearance. “There is no way they ran away. They never went far from home and were always very obedient. We feel positively sure they were taken.” Tionda knew her home phone number as well as her mother’s cell phone number, and they believed she would have called Tracey if she were able.

As evening fell on Sunday, the whereabouts of the children remained unknown. Chicago Police Youth Investigations Cmdr. Roberta Bartik admitted, “This is a long period of time for these children to be missing. We are concerned…we just want them back safe and sound.” She made a public appeal for anyone with information to contact investigators, and she also had a message for Tionda. “If she is afraid to come home because she stayed out with her sister, I would like her to know that nothing will happen to her. We’ll be very glad to get her home.”

Cmdr. Bartik told reporters that detectives were concentrating on finding the missing sisters and were not yet looking into the fact that their mother had left them unsupervised. Tracey had been cooperative in their investigation, but would eventually have to answer some tough questions about why she left them home alone.

Tracey had four children; at the time that Diamond and Tionda went missing, her other two kids were staying with their grandmother, Mary Bradley, in a nearby housing project. It was common for the four children to split their time between their mother’s apartment and their grandmother’s home; on this occasion, Diamond and Tionda had opted to stay at their mom’s while their two sisters went to Mary’s house.

Neighbors told detectives that Tionda was a familiar sight around the apartment complex, but she never strayed far from home. They noted that Tionda usually carried a set of keys to her apartment as the girls were sometimes left alone, but said that Tionda was mature for her age and very responsible.

On Monday, the FBI entered the search for the missing sisters as Chicago police feared that they had been abducted. Although they hadn’t found any evidence pointing to foul play, the fact that there had been no reported sightings of the girls since they went missing had them concerned that someone had picked them up and taken them out of the area.

Family members believed that the girls had been taken by someone they knew and trusted; Tionda was described as quite street-smart for her age and unlikely to go anywhere with a stranger. The note that she left behind was also concerning; although it had definitely been penned by Tionda, the fact that there were no grammar or spelling mistakes led those who knew the girls to believe that someone had coached her into writing it. Detectives obtained handwriting samples from Tionda’s school and sent the note to be analyzed by experts to confirm it was written by her.

As detectives continued to canvass the neighborhood, they spoke with a couple of residents who believed they had seen the two sisters playing in the area as late as 3:00 pm on Friday, just three hours before they were reported missing. If neighbors really had seen Diamond and Tionda, it was unclear why they hadn’t checked in with their mother.

A candlelight vigil was held to pray for the sisters’ safe return Monday night, and more than 200 people attended. Although Tracey declined to attend — she was still too distraught over her daughters’ disappearance — several other family members went in her place.

After the vigil was over, Pastor Corey Brooks of the New Beginnings Church told those in the crowd that he had spoken to Tracey. “She was not a negligent mother. It is very difficult when you have to raise children and put food on the table. We’re still praying and hopeful that these children are going to show up.”

Tracey seemed to be aware that she was under a cloud of suspicion. Detectives interviewed her for six hours on Saturday, eight hours on Sunday, and six hours on Monday. She was asked to submit to a polygraph examination about the girls’ disappearance, and she readily agreed. Investigators confirmed that she passed the test, but she would continue to be interviewed on a daily basis as they tried to determine exactly what had happened to the missing sisters.

By Tuesday, it was apparent that detectives were considering the possibility that the missing girls were no longer alive. They spent much of the day digging for potential gravesites in the Dan Ryan Woods while divers from the Chicago Fire Department were sent into the Washington Park lagoon after they got a tip that their bodies might be found there. They used cadaver dogs to search through dumpsters on 87th Street and horses to comb through the area surrounding two different sets of railroad tracks. Despite their efforts, they found no clues as to what had happened to Diamond and Tionda.

Investigators collected surveillance video from dozens of stores in the area where the sisters were last seen, hoping to find some sign of the girls on tape. They thought the girls might have been seen in a Jewel store on Tuesday, but after carefully reviewing the video, they determined it had been two children who resembled Diamond and Tionda. They were unable to find any trace of the sisters after they left their home on Friday.

Detectives confirmed that there were more than 100 registered sex offenders living in the sisters’ South Side neighborhood, and they meticulously tracked down each one and interviewed them about their movements on the day Diamond and Tionda went missing. They found nothing to indicate that any of them had been involved in their disappearance.

Tracey attended a candlelight vigil that was held Tuesday night, holding back tears as she addressed the crowd. “I’m wishing whoever got my kids…just return my kids home.” She left immediately after the vigil was over and went back to the police station, where investigators interviewed her for a fourth time.

Tracey told investigators that Diamond’s father had stayed at the apartment with her and her daughters the night before they went missing, and he had left with her early Friday morning as he had given her a ride to work. Police spent Wednesday searching the man’s property while he was interviewed by detectives. Investigators also interviewed neighbors of the man, asking several of them if there had been any unusual activity at the home Friday night. One neighbor said detectives asked him if he had seen any sort of fire at the residence, but he told them that everything had been quiet.

Although investigators told reporters that Diamond’s father wasn’t considered a suspect in the case, they also said they hadn’t ruled anybody out. Tracey had filed a paternity suit against the man several weeks earlier; in it, she maintained that he was the father of her youngest daughter and she was suing him for child support. It was unclear if the man was disputing her claim.

At a press briefing held Wednesday night, detectives admitted that the chances for a happy ending were growing slimmer each day. Chicago Police Deputy Superintendent John Thomas noted, “The fact that the little girls have not been located at this point certainly does not bode well.” He stressed that the department had been using all available resources to find the missing children, but they still had no idea what had happened to them.

Mike Kerns, an investigator who had worked on the Polly Klaas kidnapping case, told reporters that the sisters’ disappearance was frustrating. “You know that two young girls like that don’t just disappear off the face of the earth, but you have no idea what happened to them. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle. What haunts you is, do you have the right pieces and if you do, how do they fit together?”

As the investigation entered its second week, those close to the girls struggled to stay optimistic. The amount of manpower used in the search was staggering: more than 500 Chicago police officers, 20 members of the FBI’s Violent Crimes Task Force, 10 K-9 units from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office, and 20 officers and K-9 units from the Cook County Forest Preserve Police Department had been involved in the search effort, yet they had nothing to show for all their hard work. They had interviewed hundreds of people and sifted through more than 200 tons of trash, but hadn’t found a single clue about what had happened to Diamond and Tionda. A spokesperson for the FBI admitted, “It’s a very unusual case when you have two children disappear without a trace, no claim of responsibility, no ransom demand, just vanished.”

A week after the girls were last seen, detectives received a tip that two young girls had been seen entering an abandoned church building around the time Diamond and Tionda went missing. Investigators combed through the site, which had previously housed the New Hope House of Prayer; they did find two dirt mounds resembling graves in the basement and dug through them, but found nothing but dirt.

On Saturday, July 14, 2001, the case was featured on “America’s Most Wanted.” Family members were hopeful that the national exposure would generate some new leads for investigators. Shelia Smith told reporters, “We hope this will turn something up. They have had good success in the past.” Tracey was also optimistic that the show might lead to her daughters. “I’m just holding on. Everybody has been real encouraging. I just hope we get my daughters back home soon.”

Detectives admitted that they didn’t get as many tips as they hoped after the television show aired, but they carefully followed up on each one. For the family, it wasn’t enough. Tracey told reporters, “It’s never enough. I need more, more, more…just go out and look for my kids. It’s been 10 days…time is getting short.” She was frustrated because she felt detectives were devoting too much of their time focusing on her instead of searching for her daughters, and she insisted that she had already told investigators everything she knew.

On July 17, 2001, the Chicago Police Department announced that they were going to search through each of the city’s 5,600 abandoned buildings in an effort to find clues leading to the whereabouts of the missing sisters. It was an unprecedented effort involving hundreds of police officers, but one that Police Superintendent Terry Hilliard felt was necessary. “It’s going to continue until we come up with some type of lead on the whereabouts of these young girls.” At the same press conference, city officials announced that they were offering a $15,000 reward for information leading to the girls’ recovery.

The search of the abandoned buildings took weeks. Officers found dozens of stray dogs, hundreds of syringes, tons of garbage, and mounds of discarded clothing, but no sign of Diamond or Tionda. There was one positive note to the search effort, however: with such a heavy police presence throughout the city, crime as a whole decreased. One investigator wryly noted, “We’re killing the drug trade over here. Everyone has an interest in finding these girls and ending the search.”

As the search entered its third week, investigators finished their search of Chicago’s abandoned buildings and started using cadaver dogs to comb through each of the cars in the city’s impound lots. They found no sign of Diamond or Tionda.

By July 25, 2001, investigators had combed through much of the city but still had no idea what had happened to the missing sisters. Out of places to search, they focused on re-canvassing the South Side neighborhood with missing person flyers and re-interviewing everyone associated with the Bradley family. They continued to follow up on each tip they received, but admitted that they were running out of leads to follow. Diamond and Tionda seemed to have disappeared into thin air.

Neighbors continued to show their support for the family by holding nightly prayer vigils and marches through the apartment complex to make sure everyone knew that the girls were still missing. The lobby of the Bradley’s apartment building was turned into a shrine, filled with pictures of the missing children as well as ribbons and stuffed animals. Sheila Adams, a resident who had never met Diamond or Tionda, told a reporter, “This ordeal has brought us closer as a community. We never even used to talk to each other before.” Each resident had the same goal: to see the girls return home safely.

On Thursday, July 26, 2001, officials announced that the case was now being considered a kidnapping, though they admitted that they had no solid evidence pointing to foul play. The fact that they had been unable to find any trace of them after more than three weeks of intense searching left them with little hope that they would be found alive. Police spokesman Pat Camden noted, “It’s obvious they aren’t missing of their own volition.”

By the one-month anniversary of the girls’ disappearance, attendance at the nightly prayer vigils was starting to wane. Each day that passed made it a little harder for the family to remain optimistic about the fate of the girls, but they tried to keep their hopes up. Tracey tried to keep life as normal as possible for her other two daughters, even treating them to a day at the beach. “We can’t just waste our life in this house.”

An FBI spokesperson admitted that the case was baffling. “I don’t know if we’re any closer to finding them than the first day we got involved, but we’re still pursuing leads and working as diligently as we can.”

Officials with the Chicago Police Department assigned some of their cold case investigators to work on the girls’ disappearance, noting that they were used to frustrating cases. They were hopeful that the cold case team could find something that had been missed during the initial investigation.

After 40 days, residents of the Lake Grove Village Apartments decided to halt the nightly prayer vigils. Although they wanted to believe that the girls were still alive, after so much time they knew that it was unlikely they would be returned safely. Vickie Gilmore, a resident of the complex, noted, “Sometimes you feel so limited. All that’s left is prayer and hope, and it seems like hope is fading away.”

Tionda should have started fourth grade at Doolittle Elementary School that September, but her desk was empty. A crisis intervention team was on hand to help her classmates cope with their loss, but many of the children seemed to take the disappearance in stride. None of them stopped by to speak with counselors.

The Bradley family’s holiday celebrations were subdued that year as questions over the fate of Diamond and Tionda lingered. Hoping for a miracle, Tracey bought and wrapped presents for her missing daughters, but they remained unopened. By January, they had been missing for six months and police were no closer to learning what had happened to them. They had followed up on tips from across the country and had sent investigators as far as Florida to chase down leads. Nothing brought them any closer to the girls.

The case dominated the headlines for months, but eventually the case faded from the newspapers and the family was left alone with their grief. Tracey did what she could to keep the case in the public eye, but after so many months without any progress, the press moved on to newer stories.

Tracey grew increasingly frustrated with the lack of progress on the case. In March 2002, she was briefly detained by police after she became combative with a detective who visited the home. She pushed the detective when he asked if she would be willing to come to the police station for another interview and ended up in handcuffs. She wasn’t charged with any crime, but police admitted they were frustrated with her. “She won’t keep appointments. We’re running into a brick wall.”

Later that month, Tracey filed a complaint with the Chicago Police Department, alleging that she was physically abused and illegally detained. She claimed that police officers threw her against a fence when she refused to speak with them. As she left the station after filing the complaint, she told reporters that she hoped it wouldn’t prevent police from working with her to find her children.

Months went by, and soon the children had been missing for an entire year. The search continued, but police were running out of leads. Detectives had interviewed more than 700 people and investigated more than 660 leads. They had looked into rumors that the girls were being hidden by relatives in Minnesota and followed up on reports that they had been taken to Morocco by a man who believed he was Tionda’s father. All were dea*d ends.

More than 200 friends and family members held a prayer vigil to mark the first anniversary of the girls’ disappearance. They released 365 yellow and white balloons in honor of Diamond and Tionda and planted a memory garden in the apartment complex. The girls’ grandmother told reporters that she still expected to find them alive. “Whenever I’m on a bus, whenever I’m walking, I have my eye open. I keep thinking I’ll see them.”

There was little progress made on the case over the next several years. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children released age-progression photographs of the girls on the third anniversary of the disappearance; although a few tips were called in after the pictures were released, no new leads were developed.

In 2007, the family felt renewed hope that the girls would be found alive after they found a recent picture of a girl they believed might be Tionda on the internet. Detectives followed up on the lead but were unable to confirm the girl’s identity.

Years passed, and the girls remained missing. In 2015, their aunt Shelia admitted that she had finally accepted the fact that the girls were likely de*ad. “It’s a matter of finding out where they are.” She was convinced that there were people in the city of Chicago who knew exactly what had happened to the sisters, and she remained hopeful that they would eventually come forward so the family could have closure.

The Bradley family continues to hold yearly vigils to mark the grim anniversary of the day Diamond and Tionda went missing; the passage of time hasn’t made their loss hurt any less. The disappearance haunts the investigators who worked the case as well. Although Detective Ed Carroll retired from the police force in 2013, he has never stopped thinking about the missing girls. “It just bothers me that these two kids went missing, vanished into thin air, and we were never able to find them.”

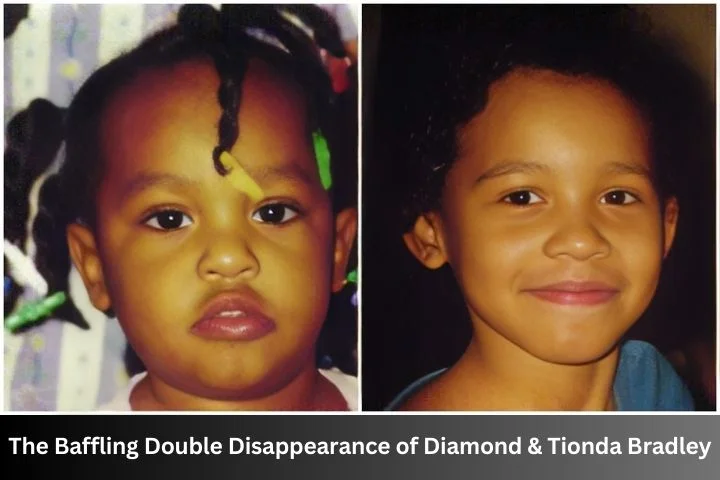

Diamond Yvette Bradley was just 3 years old when she went missing from Chicago, Illinois in July 2001. She was a happy child who enjoyed doing everything her three older sisters did. Diamond has black hair and brown eyes, and her hair was braided in the back and divided into four ponytails, which were held with purple ponytail holders. At the time of her disappearance, Diamond was 3 feet tall and weighed 40 pounds, and she had a scar on the left side of her hairline.

Tionda Bradley was just 10 years old when she went missing along with her sister, Diamond, in July 2001. She was a smart child who was mature for her age and had just completed third grade at Doolittle Elementary School a month before she vanished. Tionda has brown eyes and brown hair that she normally wore in two ponytails which were fastened with green ponytail holders. At the time of her disappearance, Tionda was 4 feet 2 inches tall and weighed 70 pounds, and she had a quarter-sized burn scar on her left forearm.

If you have any information about Diamond or Tionda, please contact the Chicago Police Department at 312–745–6007 or the Chicago office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation at 312–431–1333.