Cathy Moulton was in an excited mood on the afternoon of Friday, September 24, 1971. The 16-year-old planned to meet several of her friends at a dance being held that evening at the YWCA in downtown Portland, Maine, and she had been looking forward to it all week. She had made a new skirt to wear to the dance, but ran out of thread while she was hemming it and realized she needed to buy some more. She also wanted to pick up a new pair of pantyhose, so she asked her father if he would drop her off in Portland’s downtown shopping area, just a couple of miles from their home.

Lyman Moulton agreed to drive his daughter downtown. Before they left the house, Cathy’s mother, Claire, asked her to buy some toothpaste while she was out. She handed Cathy enough money to buy what she needed and pay for bus fare home. Cathy promised her mother that she would be home in time for dinner at 6:00 pm, then she and her father headed downtown.

Lyman dropped Cathy off on Forest Avenue around 3:30 pm. From there, she walked to Porteous, Mitchell & Braun, a large department store on Congress Street. She made her way inside and spent some time browsing through the aisles before purchasing a spool of thread, a pair of pantyhose, and two tubes of toothpaste. With some time to kill before she had to get the bus home, Cathy then decided to visit one of her friends at a local music store.

It was around 5:30 pm when Cathy arrived at the Starbird Music store on Forest Avenue. She chatted with her friend, Carol Starbird, for a few minutes before mentioning that she was going to have to walk home as she had already spent the money she was supposed to use for bus fare. She said she wanted to get home in enough time to eat dinner and get a shower before that night’s dance, which Carol also planned to attend. Cathy was in a cheerful mood when she left the music store, telling Carol that she would see her at the dance in a couple of hours.

When Cathy left Starbird Music, she headed down Forest Avenue in the direction of her home on Clinton Street, less than two miles away. It was a walk Cathy had made before and she should have arrived home in plenty of time for her 6:00 pm family dinner. She never made it home.

Cathy was a responsible teenager who always called her mother if she was going to be late getting home. The family sat down to dinner together every night promptly at 6:00 pm; Cathy and her two younger sisters never missed a meal. When Cathy failed to show up in time to eat, Claire instantly feared that something was wrong. She and her husband grew increasingly anxious as the minutes ticked by with no word from their oldest daughter.

Claire started calling all of Cathy’s friends but none of them knew where she might be. In desperation, Lyman started driving up and down the streets of downtown Portland, searching fruitlessly for any sign of his daughter. Finally, he returned home and told Claire that they needed to involve the police. Claire called the Portland Police Department and explained the situation, but the voice on the other end of the line told her she couldn’t fill out a missing person report until Cathy had been gone for at least 72 hours.

Lyman then drove to the Portland police station and insisted on reporting his daughter missing, but the officer on desk duty that evening dismissed his concerns. Cathy was a teenager in 1971, a time when the hippie movement was still going strong. The general attitude of law enforcement at the time was to assume that any missing teenager simply ran off to join a commune somewhere. The officer told the worried father to come back to the station if he didn’t hear from his daughter after a few weeks.

Lyman was justifiably furious. He was certain that something had happened to his daughter and couldn’t believe that law enforcement wasn’t willing to look for her. He drove back to the police station the following morning and demanded to speak with someone who would be willing to take a missing person report. Sensing the irate father wasn’t going to take no for an answer, an officer did file a missing person report on Cathy but police still refused to launch an active search for her.

To those who knew Cathy, the idea that she was a runaway was ridiculous. Except for her purse, she didn’t have any of her belongings with her. She didn’t even have enough money to pay for bus fare home, let alone to finance a trip out of the city. It was absurd to think the sensible teen would run away with nothing more than the clothes on her back, some thread, and a couple of tubes of toothpaste. Despite this, police refused to consider the idea that she might have been abducted.

Outside of a single mention in a local newspaper, Cathy’s case received no publicity when she first went missing. Incredibly, on October 5th, a spokesperson for the Portland Police Department said that Cathy’s case was at a standstill, despite the fact that they hadn’t conducted even a cursory investigation into her disappearance. “We just don’t know what happened. She just dropped from sight.” Frustrated by the lax attitude of the Portland police, the Moultons hired a private investigator to help them find their daughter.

At the time of her disappearance, Cathy was a junior at Deering High School, where she was a popular and bright student. She loved writing poetry and sewing her own clothing, and she was close with her two younger sisters. Her mother had given up a career as an emergency room nurse to become a stay-at-home mom, and Cathy was extremely close with her. The two would chat for hours when Cathy got home from school and Claire assumed that her teenage daughter kept no secrets from her.

Lyman owned a used car lot and service station, but he had taken the summer off from work so he could treat his family to a cross-country vacation. It had been the trip of a lifetime for Cathy and her sisters; the family had spent nearly three months driving from coast to coast across the United States and into Mexico. Cathy had celebrated her 16th birthday while they were in Williamsburg, Virginia; later in the trip, when the family reached Texas, she had picked out a unique leather purse as her birthday gift. She was carrying it on the day she disappeared.

Outside her home, Cathy was starting to become a little rebellious but this side of her was hidden from her parents. She wasn’t a bad teenager, just one who was eager to start asserting her independence as she got older. She had recently started smoking cigarettes; it’s possible that she had used her bus fare to buy a pack and that’s why she had to walk home. Although it wasn’t something her parents would have approved of, smoking was very common among teenagers at the time and not seen as a huge vice.

Unbeknownst to her parents, Cathy had also started hanging out at a local coffee shop, The Gate, known for attracting an eclectic crowd. It was at The Gate that Cathy met Chris Church, a Portland photographer. He offered to do a photo shoot of her in his studio, and Cathy had happily agreed. Although he later admitted that he had been interested in the teenager, she already had a boyfriend and Chris didn’t push the issue.

Cathy’s boyfriend was yet another secret she was keeping from her parents. It’s unclear exactly how she met 22-year-old Lester Everett, but it was likely at The Gate. Lester was known to local police as somewhat of a troublemaker but not one who had been in major trouble with the law. Still, he wasn’t someone any parent would want their 16-year-old daughter dating.

Days turned into weeks, then months, and there was still no sign of Cathy. Since her parents had no idea that she had been spending time at The Gate and dating an older man, they weren’t able to provide this information to investigators. This meant that crucial potential witnesses were never spoken to as no one knew they existed. It would take years before Cathy’s habits in the weeks leading up to her disappearance would come to light.

Lyman and Claire resigned themselves to the fact that police likely weren’t going to find their daughter but refused to give up on the hope that she would return home safely. They spent their free time distributing missing person flyers throughout Portland and following up on every tip and rumor they heard.

A neighbor believed she had seen Cathy, accompanied by two unknown males, in a Bangor shopping mall the day after she was last seen in Portland. Since the neighbor was unaware that Cathy was missing, she hadn’t thought much of it at the time. Later, she noted that Cathy hadn’t seemed to be in any kind of distress but since she hadn’t spoken to her, the neighbor could not say for certain. Although this sighting fueled speculation that Cathy had willingly run away from home, her family refused to believe it. They were adamant that Cathy would have reached out to them if she were able and feared that she was being held somewhere against her will.

Later, someone claimed to have spotted Cathy on Presque Island, prompting Lyman and Claire to immediately get in their car and make the four-hour drive there. When they spoke with local police officers, they were dismayed to realize that they had no idea Cathy was missing as her disappearance hadn’t been publicized. They left missing person flyers at the station and hung up posters around the town, but there were no further sightings of Cathy.

Cathy’s disappearance languished in the cold case files for more than two decades. When Kevin Cady joined the Portland Police Department in 1985, he had no idea who Cathy Moulton was. A decade later, her case would find its way to his desk and he was immediately obsessed with finding out what happened to her.

When Detective Cady first looked at Cathy’s case file in 1995, he was underwhelmed. It consisted of only a few pages of paper: the original missing person report filed by her father and a report detailing a Jane Doe found in British Columbia who matched Cathy’s description but was ruled out as being her after dental records were compared. There was nothing else. Not a single witness statement, tip, or investigative lead had been recorded. Cady and his supervisor, Sgt. Tom Joyce, would have to start from scratch.

Cady decided to start with the people who had been closest to Cathy at the time of her disappearance. He tracked down her best friend, Nancy Barlow, one of the people Cathy had planned to meet at the YWCA the night she vanished. Nancy was able to provide a lot of insight into Cathy’s life in 1971. She was the first person to mention The Gate and Lester Everett, which sent the investigation in a completely new direction.

There had long been rumors that Cathy had been seen getting into a car with a man shortly after she left the Starbird Music store. After speaking with dozens of people, Cady was eventually able to confirm that the man driving the car had been Lester Everett. Working tirelessly, Cady was able to piece together what had happened after Cathy got into Lester’s car.

It seems likely that Cathy had accepted a ride with Lester because she assumed he was going to take her home. Instead, Lester picked up a hitchhiker, a Canadian man by the name of Reid Perley, who was standing on the side of the road thumbing a ride. Reid told Lester that he was going to New Brunswick in Canada. Incredibly, Lester decided to drive this man — who he had never met before — to his destination more than five hours away.

After viewing photographs, Cathy’s neighbor was able to identify Lester and Reid as the two men she saw with Cathy in a Bangor shopping mall 25 years earlier. Since she didn’t speak with Cathy, there was no way of telling if the teenager was there against her will, but detectives believe that she was forced to remain with the two men. She had been so excited about going to a dance that Friday night; if she had been able to get out of the car in Portland, those who knew her are convinced she would have.

The next sighting of Cathy was at a gas station in Aroostook County, Maine. Don Logan, who had worked as a mechanic at Dorsey’s Garage in the 1970s, recalled seeing Cathy, Reid, and Lester at the station shortly after Cathy went missing. Lester had been driving a Cadillac that needed new tires and they waited at the garage for the tires to be installed. Don noticed that Reid had his hand on Cathy the entire time, as if he were afraid she might try to run if given the chance. When she needed to use the restroom, he guided her there with his hand on the back of her neck.

The mechanic had no idea Cathy was a missing person; the only reason the trio made a lasting impression on him was that a detective had visited the station a couple of weeks later and informed the mechanic that both the Cadillac and the credit card used to buy tires for it had been stolen from the owners of the Davis Motel in Falmouth, Maine. Suspicion had immediately fallen on Lester, who had worked at the motel. Unfortunately, by the time police learned that the credit card had been used at Dorsey’s Garage, Lester was long gone.

A week after Cathy was last seen, she and Lester turned up at McBride’s Farm in Mars Hill, Maine, located next to the Canadian border. They had apparently taken Reid to his home on the Tobique First Nation Reservation in New Brunswick, Canada, and left him there before returning to the United States. Lester had been careful to use back roads in order to avoid going through any border checkpoints.

Many members of First Nation tribes arrived at the Mars Hill farm each fall to help with the potato harvest. It’s not entirely clear why Lester chose to bring Cathy there; he was not popular with the other workers, who viewed him as lazy. Cathy did make one friend on the farm, a young woman named Millie Augustine. She confided in Millie that she was afraid of the men working on the farm; she also cried a lot and said that she wanted to go home. She spent all of her time in Lester’s stolen Cadillac, which had become her only form of shelter.

Eventually, Lester seemed to have tired of Cathy’s constant pleas to return to Portland. Taking her there wasn’t an option for him; he knew if he showed up in Portland with her he would be arrested on kidnapping charges. Instead, he drove her across the Canadian border and left her on the Tobique reservation with Reid. It’s possible he thought she would prefer living in Reid’s house to living out of his Cadillac; whatever his reasons, he returned to Mars Hill alone and remained there until the potato harvest was over.

After the potato season finished, Lester told some of the other workers that he was going to Florida to pick oranges. A few of the workers thought this sounded like a good deal and opted to make the long drive to Florida with him. Once they arrived, it became clear that Lester had no jobs lined up; chagrined, the other workers headed back north while Lester remained in Florida for the next three years.

Lester eventually returned to Portland and attempted to contact Cathy. He appeared genuinely shocked when he learned that she had never made her way back home; he was so concerned that he and a friend drove back to Canada to see if she was still with Reid. She wasn’t there and Reid was not happy to see Lester. When he confronted Reid about Cathy, demanding to know where she was, Reid and one of his brothers beat him severely, stole his boots and leather jacket, and warned him to never return to the reservation.

Detectives would later conclude that Lester truly didn’t have any idea what had happened to Cathy, though this didn’t make him any less culpable in her abduction. Unfortunately, Lester died of cancer in 1985 and was therefore unable to be questioned by Det. Cady.

Det. Cady attempted to speak with Reid, but he insisted that he had no idea who Cathy was and refused to answer any questions. Reid’s sister, however, did identify a picture of Cathy and recalled that she had been at their home in the autumn of 1971. Other residents of the reservation also recognized her photograph and referred to her as Reid’s girlfriend.

In 2015, Det. Cady returned to Canada and spoke with a tribal elder who recalled a disturbing story: sometime in the late fall of 1971, she had observed Reid dragging a woman into a wooded area. The woman had been crying and attempting to fight Reid off; although it was impossible to know if this was Cathy, Det. Cady believes it was. Investigators, aided by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, conducted several searches of the wooded area surrounding the reservation but were unable to find any trace of Cathy.

Det. Cady believes that Cathy is dead, most likely kil*led by Reid sometime around Thanksgiving 1971. He admits that he has no evidence to prove this — Reid has consistently denied knowing Cathy and will not cooperate with investigators — and he is open to other theories. There were rumors that Cathy had been k*illed by one of Reid’s uncles; investigators also had to consider the distasteful possibility that she had made it home and had been k*illed by her father. They found nothing to support this and do not believe Cathy ever made it off the reservation alive.

Since he was first assigned to Cathy’s cold case file, Det. Cady desperately wanted to obtain closure for Cathy’s family and justice for Cathy. He retired from the Portland Police Department in 2005 and now works as a private investigator; he was so consumed by Cathy’s case that he wrote a book about it. Although he believes he knows what happened to her, he admits that unless her body is found, Cathy’s case will remain unsolved.

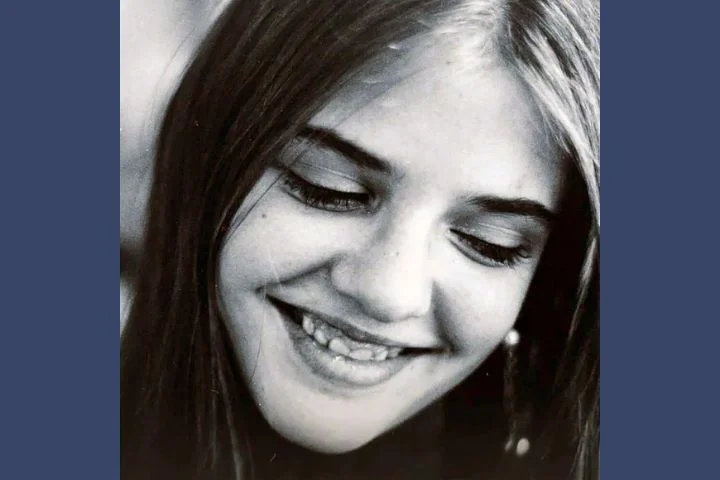

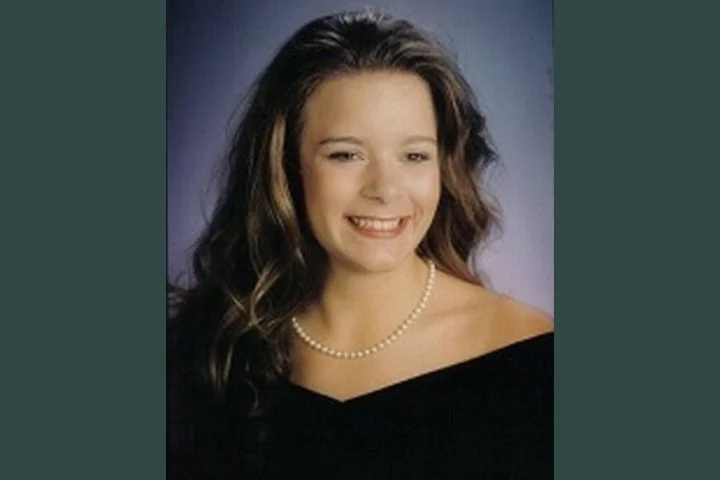

Cathy Moulton was just 16 years old when police believe she was abducted and later mur*dered. She was a sweet and sensitive teenager who loved taking care of children, dancing, and writing poetry. Although she had developed a slight rebellious streak, she was still an excellent student who was extremely close with her family.

Cathy has blue eyes and brown hair, and at the time of her disappearance she was 5 feet 4 inches tall and weighed 98 pounds. She was last seen wearing a navy blue dress, a navy blue coat, and brown leather shoes and was carrying a distinctive brown leather handbag. She had braces on her teeth and wore thick glasses. It is believed she was taken from Maine into Canada and likely k*illed there. If you have any information about Cathy, please contact the Portland Police Department at 207–874–8479.