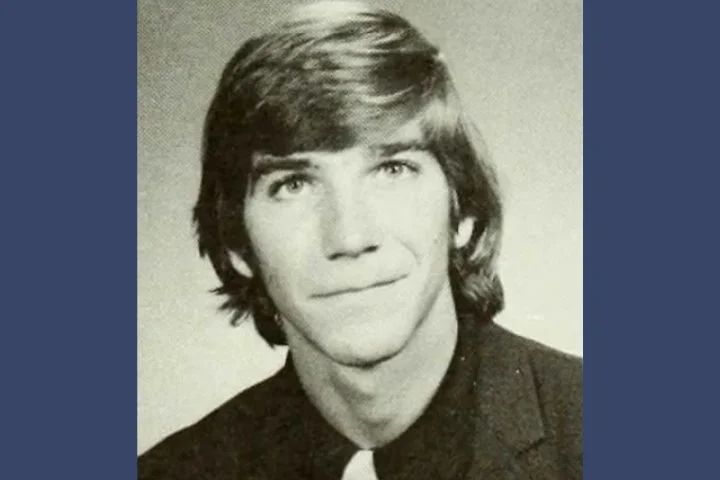

Kyle Clinkscales spent the afternoon of Tuesday, January 27, 1976, at his parents’ home in LaGrange, Georgia. The 22-year-old was a junior at Auburn University and had his own apartment in Auburn, Alabama, but he made the 40-mile drive to his hometown twice a week so he could work at his part-time job as a bartender at the Moose Club.

Kyle left his parents’ house shortly before 4:00 pm and arrived at the Moose Club a few minutes later. When his shift was over at 11:00 pm, he said goodbye to his co-workers and headed outside to the parking lot. His manager saw Kyle unlock his 1974 Ford Pinto and climb inside, presumably to make the 45-minute drive back to his Auburn apartment. He never arrived.

Kyle and his roommate, Phil Langford, had different schedules and it was common for the two to go days without seeing each other. Because of this, Phil had no idea that Kyle had failed to return to Auburn that Tuesday night. Kyle’s parents, John and Mary Louise, were slightly worried when they didn’t hear from him for a few days, but they assumed that he was just busy with classes.

Mary Louise had done some of Kyle’s laundry and had been ironing his clothes when left to go to work Tuesday night; Kyle told her that he would stop by the house before his bartending shift on Friday night to pick up his clothing. When he didn’t show up on Friday, his father called the Moose Club to see if Kyle had made it to work and was told that he had the night off. Although it was out-of-character for Kyle to take time off from work, John recalled that he had mentioned going to Gainesville, Florida to watch a basketball game. Kyle’s parents assumed that he was spending the weekend in Florida and would get in touch with them when he returned.

Kyle was scheduled to work at 4:00 pm on Tuesday. Mary Louise spent the afternoon waiting expectantly for the sound of his car pulling up outside, but he never arrived. Mary Louise called the Moose Club and was distressed to learn that Kyle hadn’t shown up for his scheduled shift; it was the first time Kyle had ever missed work without calling ahead of time. Panic set in as Mary Louise realized that no one had spoken to Kyle since the previous Tuesday night. He had been missing for a week and no one had noticed.

John called the LaGrange Police Department and reported his son missing that afternoon. After speaking with the manager of the Moose Club, investigators learned that Kyle hadn’t been in a great mood when he left work the previous Tuesday night. Although he normally got along well with all of his customers, he had to deal with a particularly obnoxious man that evening and had been extremely annoyed about it. His manager told investigators that he believed Kyle might have had a couple of drinks after the man left, but he hadn’t appeared to be intoxicated.

After learning that Kyle had been drinking, detectives theorized that he might have gotten into some kind of accident on his drive home. State police in Alabama and Georgia spent hours driving along every possible route that Kyle might have taken that night, but found no signs of a car driving off the road.

No matter which route Kyle took from LaGrange to Auburn, he would only have passed one body of water, the Chattahoochee River. At the time he went missing, the river was only ankle-deep, eliminating the possibility that he might have driven into the water and drowned. Investigators scoured the area anyway but found nothing.

John and Mary Louise told detectives that there was no way Kyle would have voluntarily disappeared without telling anyone, but investigators were unconvinced. They hadn’t found anything to suggest that foul play had taken place; they believed that Kyle had likely decided to take some time to himself and would return when he was ready.

Kyle was a 1972 graduate of LaGrange High School. He had been a skilled athlete and earned varsity letters in basketball and baseball. He was well-liked by his classmates and teachers and never caused any problems in school. He had a great relationship with his parents and was an active member of First Baptist Church in LaGrange.

Friends noted that Kyle hadn’t been doing well in college; they believed that he hadn’t really wanted to go to college but had done so because his parents expected him to get a degree. He had enrolled in Auburn University right after he graduated from high school but had done poorly; he transferred to LaGrange College but hadn’t done much better there and ended up dropping out.

Kyle had returned to Auburn University in the fall of 1976 and changed his major from education to business administration. His fall semester grades hadn’t been great, but he told his parents that he was determined to do better when he returned for the spring semester. They told investigators that if Kyle had wanted to drop out of college they would have supported his decision; they were certain that he wouldn’t have run away because of it.

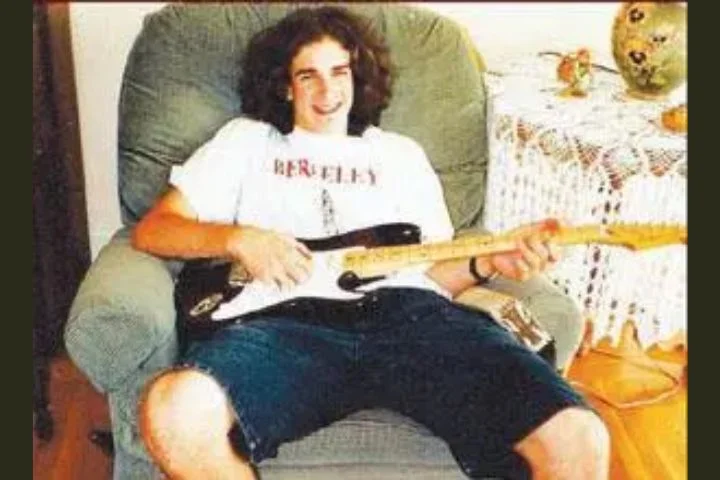

None of Kyle’s belongings were missing from his apartment. All of his clothes and personal items were left untouched in his bedroom, and he had purchased groceries, cat food, and a house plant two days before he vanished. He also left behind his two beloved cats, Queenie and Eicher; he was devoted to his pets and no one believed he would have voluntarily disappeared without taking them with him.

Shortly before Kyle went missing, he had signed up to play in a summer softball league and told friends he was looking forward to it. He had also been excited about an upcoming Valentine’s Day dance and had already gotten a date for it. He hadn’t given any indication that he was thinking about running away.

Kyle’s manager at the Moose Club told investigators that Kyle was extremely nice and very intelligent; he got along well with all of his co-workers and customers. He was the kind of person who went out of his way to be nice to everyone and was a great listener. A waitress who had been working with Kyle on the night he went missing noted that he had appeared to be somewhat agitated when he left; she had assumed that it was due to dealing with an obnoxious customer. When she asked him if he was okay, he had waved her off and told her he would tell her more when he saw her on Friday.

Officials with the LaGrange Police Department admitted they were baffled by the case. Although they had no evidence of foul play, Kyle didn’t appear to be the kind of person who would run away without warning. They appealed to the public for help in locating Kyle’s white Ford Pinto, which they believed would be the key to solving the case. As months went by without any sightings of Kyle or the car, detectives admitted that they weren’t sure if he had left the area voluntarily or not.

Kyle was the type of person who wouldn’t hesitate to pick up a hitchhiker, and some of his friends worried that he might have stopped for the wrong person. Investigators noted that it was possible Kyle had been killed for his car and doubled their efforts to find it, but despite listing it as stolen in national databases, its location remained a mystery.

As months went by, the investigations stalled and the case eventually went cold. Although investigators were no longer actively looking for Kyle, his family refused to give up the search. His parents took out numerous newspaper ads asking for help in locating their son; a year after he went missing, they announced that they were offering a $2,000 reward for information leading to his whereabouts.

John and Mary Louise belonged to a camping club called Troup Travelers and they appealed to fellow club members for help. They made bumper stickers that read “What Happened to Kyle Clinkscales driving a 1974 Pinto? Murd*ered? Amnesia?” and included a phone number to call with tips. They mailed the stickers out to members of Troup Travelers and the National Campers and Hikers Association and asked them to stick them on a prominent place on their vehicles. Soon, thousands of cars, campers, and RVs were displaying Kyle’s bumper sticker and tips began to trickle in to his parents.

By 1980, dozens of people had called from all over the country to report seeing a person matching Kyle’s description. John followed up on all the tips he received, desperate to find his son. Although he initially hoped that Kyle had just become overwhelmed with school and had taken off to clear his head, in his heart he knew this wasn’t the case. As time went by, he started to believe that Kyle was likely dead but still followed up on all leads. Unfortunately, none of the tips led to Kyle.

Kyle’s case remained cold for more than a decade. In May 1987, investigators got their first potential break, when a Troup County man who was out walking his dogs found an Exxon credit card belonging to Kyle. He had found the card near Flat Shoal Creek, which was located to the south of LaGrange. Bizarrely, despite the passage of time, the credit card was in pristine condition.

Detectives were confused by the card’s excellent condition and theorized that it had likely been buried until shortly before it was found. They noted that it had expired in 1973, three years before Kyle had gone missing. His parents recalled that Kyle’s wallet had been stolen while he was attending LaGrange College; this card might have been in his wallet at that time. Kyle often forgot to get rid of his expired credit cards, however, so it could have been in his wallet when he went missing.

Investigators conducted a large-scale search in the area where the credit card had been found. They recruited county prison inmates to help dig along the sandy creek bank, while the Georgia State Police dispatched a helicopter crew to search the length of the creek from the air. They found nothing to indicate that Kyle’s body was buried in the area.

After the failed search, the investigation went cold once more. After a local newspaper published an article on the 20th anniversary of the case in 1996, several new tips were called in to investigators. After following up on one of these tips, detectives found car parts that they believed might have belonged to Kyle’s 1974 Pinto.

Another tip sent deputies from the Troup County Sheriff’s Office to Stovall Lake; an anonymous caller claimed that Kyle had been killed and his body dumped into this lake. Investigators spent two days draining the lake, which was located on private property, then used metal detectors and cadaver dogs to search the lake bed.

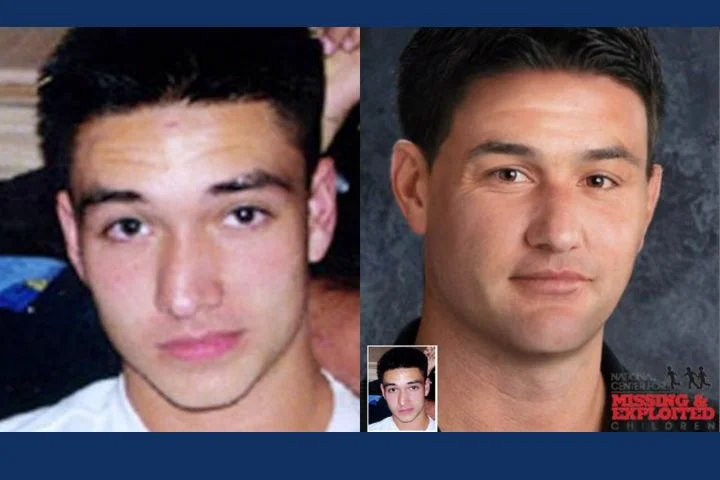

Although detectives refused to name any suspects, they told reporters that if they did find Kyle’s body, they were prepared to charge more than one person with his m*urder. Ray Hyde, who owned a local junkyard, then came forward and told reporters that he was the prime suspect. There had been several rumors over the years implicating Ray in Kyle’s de*ath, but he insisted that he had absolutely nothing to do with the disappearance.

Ray’s home and junkyard were located just a mile away from Stovall Lake. While the search of the lake was taking place, the Troup County Sheriff’s Office executed a search warrant on his property. Ray continued to proclaim his innocence and told reporters that the police had no evidence against him. He also noted that he would never be stupid enough to dispose of a body in Stovall Lake. “I’d dump it off the Georgia coast weighted down with a couple of electrical transformers where the sharks could eat it.”

Ray’s confidence only grew when detectives admitted that they had not found anything connected to Kyle’s disappearance during their search of the lake or Ray’s property. Although it was clear they still believed that Ray had done something to Kyle, they were unable to prove it and the case went cold yet again.

Nearly a decade later, in April 2005, John and Mary Louise got a call from a man who claimed he knew what happened to Kyle. The caller, who had been a 7-year-old child when Kyle went missing, stated that he had witnessed his grandfather taking part in the disposal of Kyle’s body. He claimed that Kyle’s body had been placed in a barrel, covered with concrete, and then placed in a pond.

Investigators drained the pond in question but were unable to find a barrel or Kyle’s body. They did find a spot where it appeared a barrel had once been, but it appeared that it had been removed at some point over the years. Despite the lack of evidence, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Jimmy Earl Jones, a 63-year-old man who had once been associated with Ray Hyde. Jimmy was charged with a variety of cri*mes, including concealing a de*ath and making false statements, but he was not charged with mu*rder.

Detectives believe that Ray Hyde m*urdered Kyle, but he died in 2001 without ever confessing to the cr*ime. While they still don’t know why Kyle was targeted for mu*rder, they believe that he likely overheard something that got him killed. Ray was a member of the Moose Club and frequented the bar there; he was also deeply involved in crim*inal activities. Six months after Kyle went missing, Ray was convicted of numerous auto theft charges; detectives believe that Kyle may have overheard Ray discussing where the stolen cars were concealed. Ray was also involved in the drug trade and it’s possible that Kyle witnessed some kind of drug deal that later got him killed.

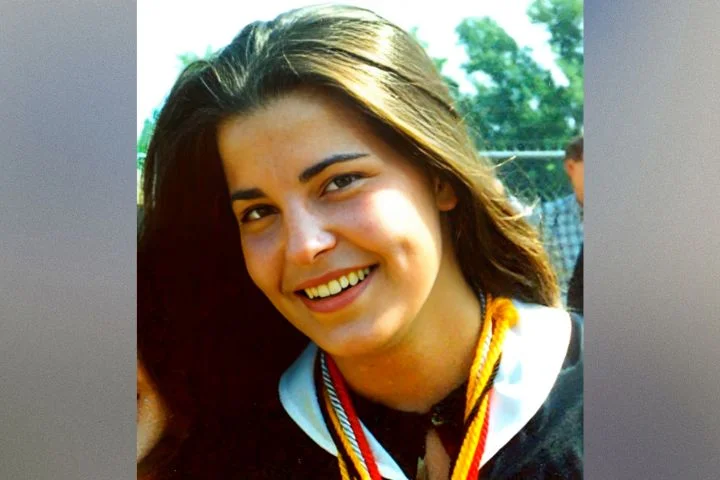

Although Kyle’s case remains open, the investigation is no longer active. Detectives believe that Ray killed Kyle and enlisted several others to help him dispose of the body, but they have never been able to locate Kyle’s remains. Until his remains are found, his friends refuse to let go of the hope that he is still alive somewhere. John Clinkscales died in 2007 and Mary Louise died in 2021, hoping until the end that her son would be found.

Kyle Clinkscales was 22 years old when he went missing in 1976. He has hazel eyes and brown hair and at the time of his disappearance, he was 5 feet 11 inches tall and weighed 156 pounds. He was last seen wearing a multi-colored shirt, blue jeans, a white tie, and a denim or suede jacket. If you have any information about Kyle, please contact the Troup County Sheriff’s Department at 706–883–1746.