It was a cold Saturday in early November, but eight-year-old William Majewski wanted to go fishing. The second-grader had spent most of the day playing outside, returning to the home he shared with his mother and four siblings just long enough to eat a quick dinner around 4:00 pm. As soon as he finished, he asked his mother if he could go back outside and play some more. William was Alice Stubenrauch’s middle child, and he was a well-behaved boy who rarely got into any trouble. She told him he could go back out as long as he was home before dark. Their small town of McKees Rock, Pennsylvania was considered a safe place for children to play outside. He pulled on a hooded sweatshirt and headed out the door.

Around 10:30 pm, police received a frantic call from Alice. William was missing. She told police that she had become worried when William hadn’t returned home by 6:30 pm. She didn’t drive but said she had walked all over looking for him before admitting defeat and calling the police. Friends of William told police that they had seen the boy earlier on Saturday, and he had told them that he planned on going fishing later that day. Other neighbors confirmed seeing the boy around 4:30 pm. He had been carrying his fishing gear and was headed in the direction of Chartiers Creek.

A search party was quickly formed, and it took only a few minutes for them to locate William’s fishing gear. It was found only a block away from his home, at a spot where he and his brothers would often go fishing. There was no sign of any kind of struggle, and none of William’s fishing gear seemed to be missing. They did a preliminary search of the creek area but were unable to find anything in the darkness. Bloodhounds were brought in, and they were able to pick up William’s scent along the creek bank and in the water. The dogs were able to track the scent for about 200 yards downstream from where William’s fishing gear had been found. Police feared that the boy had fallen into the water and drowned, but they would need to wait until the sun came up before they could complete a comprehensive search.

The following morning, more than 100 people gathered to search for William. Police officers and volunteer firefighters scoured the area along the banks of the creek, and divers searched the cold water for any sign of William. With temperatures hovering around freezing, divers couldn’t stay in the water for long. A heated bus was provided by the Port Authority Transit so that the divers had somewhere to warm up in between dives. Members of William’s family also used the bus, anxiously watching the search teams from the windows.

Early in the search, there had been a flurry of activity after searchers found what appeared to be blood on a rock near William’s fishing gear. A technician from the county crime lab was sent to the scene to do some tests, but they determined that the stain was not human blood.

The search effort was hampered by weather. Heavy rains had been falling, and this caused the current in the creek to become dangerously strong. It also kicked up so much mud in the creek that divers had zero visibility in the water. They were forced to crawl along the creek bottom and use their hands to search. A sonar unit was brought in to assist them, but the current had become so strong that the divers were unable to stay in one spot long enough to complete a thorough search. They were pulled yards downstream from where they entered the water in a matter of seconds. Despite the difficult conditions, the search teams persevered. Many were parents themselves, and none of them wanted to stop until William was found.

Alice told police that she didn’t believe that William had drowned. As much as he loved to fish, he didn’t know how to swim and was actually somewhat afraid of the water. He would normally go fishing with his brothers, and he never went into the water. Although their fishing spot was only about 200 yards from where the creek met the Ohio River, the spot was not considered to be dangerous and William knew how to be safe around the water. Alice believed that someone must have snatched her son, but police could find no evidence that an abduction had taken place. Since William’s fishing gear had been found near the creek, they knew he had been there at one point on Saturday. They would continue to concentrate the majority of their search efforts there.

By Monday, there were more than 150 rescue workers involved in the search for William. A team of 40 divers took turns searching the creek, beginning at the spot where William’s fishing gear had been found and continuing 600 yards in either direction. When darkness fell, the search was called off. The McKees Rock fire chief, Ed Maritz, told reporters that if William had ended up in the creek, they would have found his body by then. He explained that not even increased currents in the creek would have been enough to carry the boy’s body into the Ohio River. If William had fallen in, his body would have remained in close proximity to where he fell in. The police chief, Robert Martineau, agreed. If William had drowned, his body should have surfaced by that point. Detectives still weren’t sure what had happened to the boy, but they didn’t believe he died in the water.

Investigators began canvassing the city, looking for anyone who might have seen William on the day he disappeared. Witnesses gave conflicting reports, and detectives weren’t sure who to believe. Many of the people they spoke to were familiar with William, and all described him as a friendly, good kid who never got into trouble. Quite a few of them believed they had seen the little boy that Saturday. Some said he had been walking towards the creek with his fishing gear, a claim that was backed up by the evidence obtained during the search. But others said they had seen him at the McKees Rock plaza, a nearby shopping area. A couple of people believed they saw William in a local store, talking to a scruffy-looking man that they didn’t recognize. One witness told police a particularly disturbing story, claiming they had seen William being pulled into an orange Nova by an unkempt man. It’s unclear why they didn’t call the police at that time if they believed he was being abducted.

As investigators were trying to come up with a timeline for where William had been on that Saturday, they realized that his mother had not been entirely honest with them. Alice had told detectives that she had realized William was missing around 6:30 pm on Saturday night, and she spent four hours searching for him before finally calling the police to report him missing. There were some who had been skeptical of this story from the beginning. William’s fishing gear was found a mere block from his home. If Alice had spent four hours searching, how had she missed it? Detectives soon learned that Alice had been lying to them about the events of that night. She had spent her Saturday night playing Bingo, and it wasn’t until she came home at 10:30 pm that she realized William was missing. She didn’t attempt to search for him at all. The investigators weren’t sure why Alice lied to them, though they suspected it was to make herself appear to be a more attentive mother than she actually was. Whatever the reason, it meant that detectives would now question everything she told them.

As news spread about William’s disappearance, police were overwhelmed with calls concerning possible leads. Some seemed too outlandish to be true — one caller insisted that William’s family had sold him to gypsies — but detectives thoroughly investigated each one. They tracked down known pedophiles in the area but could find none that appeared to have crossed paths with William. Helen Arlott, a good friend of Alice, told police that William was a frequent visitor in her home. She had never seen any signs that anything was wrong, and she believed that Alice was a great mother.

Two weeks after William disappeared, the investigation seemed to be at a standstill. Repeated searches of Chartiers Creek failed to yield any sign of the boy, and detectives felt fairly certain that he had not drowned. They were left with two possibilities: William had either run away from home or he had been abducted. Based on what they learned in conversations with those who knew William, they didn’t believe he would have run away. He was only eight, and there was nowhere for him to run to. He had no problems in his life, and he was close with his family, especially with his 10-year-old brother Stephen. Most of the investigators believed that abduction was the most likely scenario, but they could find no evidence to back up that theory, either. William had simply vanished without a trace.

Less than a month after William went missing, Alice packed up her family and moved away from McKees Rocks. It wasn’t a far move — they settled in the small community of Hazelwood, about 20 minutes away — but Alice felt it was necessary for the sake of her four remaining children, who were struggling to get on with their lives after the disappearance of their brother. Detectives claimed she never contacted them to check on the status of the investigation. When they decided to do one more search of the creek on December 11th, Alice was unaware of it until a reporter called to get her opinion about it. She was furious. She told reporters that it was ridiculous that everyone else knew about the search before she did. She insisted that there was no reason for another search of the creek as she believed that William hadn’t drowned. She was sure he had been abducted. She was at least partially right. Authorities still had no evidence proving that William had been abducted, but they didn’t find anything in their search of the creek, either.

Tension continued to simmer between Alice and the investigators. It finally boiled over in May of 1992. Detective Donald Panyko, who had been in charge of the investigation from the beginning, told reporters that he believed William’s family was hiding something, and that they hadn’t told them everything they knew about the night he went missing. Alice was livid when she saw the interview on television, and she called Detective Panyko to complain about his remarks. He noted that it was the first time she had ever contacted police during the search for William, though he didn’t come right out and say that her lack of concern about the investigation seemed to indicate some level of involvement. Reminding Alice that she had given inconsistent stories about what happened on the night William went missing, he asked if she would be willing to take a lie detector test. She agreed, and the test was scheduled for noon on May 12th. She never showed up.

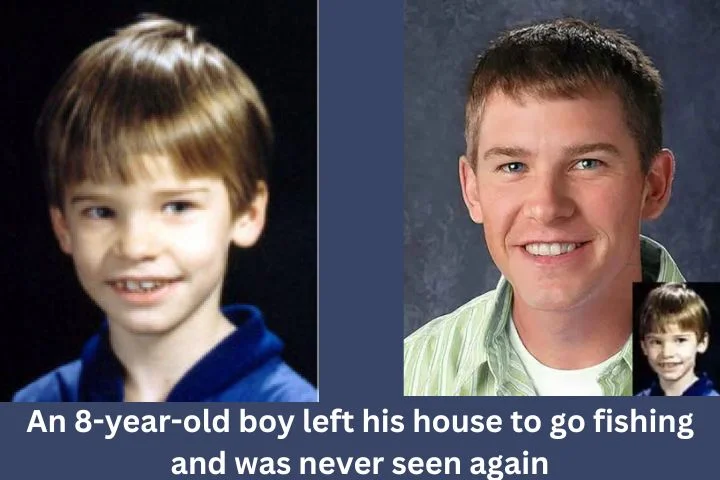

Despite her refusal to take a lie detector test, detectives never believed that Alice had done anything to her son, though they did think it was possible that she knew more than she was telling them. Her initial statements to police were no doubt driven by fear and perhaps even some guilt that she had been out late that Saturday night when William went missing. William was one of five children, and there were never any allegations of abuse in the household. There were many in the community who knew William — they affectionately referred to him as Willie — and they all said he was a sweet and well-behaved child. They never saw any indication that he had any problems at home. William’s disappearance was tragic, but it is doubtful that Alice had any part in it.Age progression of William showing what he may have looked like as a teenager (Provided by NCMEC)

Years went by, and the investigation into William’s disappearance eventually went cold. It was still periodically reviewed by detectives, but they knew that their chances of solving it decreased as time passed. Then, in September of 2000, there was a potential break in the case. Scott Drake, an 11-year-old boy from East Allegheny, disappeared while riding his bicycle around the neighborhood on a Sunday afternoon. His mutilated body was discovered later that night, and a homeless man soon confessed to the crime. Joseph Cornelius was known to hang out in the area where the body was found, and he told investigators that he had killed Scott after the boy tried to steal his radio. He then decided to mutilate the body so that police would think that the boy had been killed by a pedophile.

The case caught the eye of detectives who had been involved in investigating William’s disappearance once they realized that Joseph had lived in McKees Rocks at the time that William went missing. He had been dating Helen Arlott, who had been good friends with Alice. Detective Panyko had interviewed Helen shortly after William had gone missing, and Joseph, who was living with Helen at the time, had sat in on the interview. Joseph had never been considered a suspect in William’s disappearance, but once he was arrested for the murder of Scott Drake, investigators decided to take another look at him. They were at a disadvantage because so many years had gone by. Helen had died a couple of years before, and none of the detectives knew how to get ahold of Alice, who had long since cut ties with McKees Rocks and its police department.

In the end, Joseph was never charged in William’s disappearance. He denied all accusations, and detectives simply had no evidence to prove he did it. Detective Panyko, who was retired at that point, said that he doubted Joseph had been involved, but agreed that they may never know for certain. The only thing they know for sure is that William walked out of his home that cold afternoon more than two decades ago and then vanished without a trace.

William Majewski was eight years old when he disappeared from McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania. At the time, he was about 4’1” and weighed around 50 pounds. He is a white male with sandy brown hair and blue eyes. His adult teeth were still coming in when he went missing, and they were crooked and had gaps in between them. When last seen, he was wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt, gray sweatpants, and black sneakers. If you have any information about William, please contact the McKees Rocks Police Department at 412–331–2300.