Sandra Ross left her Apex, North Carolina home around noon on Sunday, January 8, 1984. The 31-year-old planned to go to a nearby pharmacy to pick up a prescription for her 15-month-old daughter, who had been sick that morning, and then buy some groceries. Sandra drove off in her 1976 Chevrolet Chevelle and headed in the direction of the Cary Village Mall, where the pharmacy was located. She never returned home and she was never seen again.

Sandra’s husband, Robert Ross, grew concerned when she wasn’t back after an hour or so. He bundled his daughter up against the cold, then got her settled into his car and drove to the Cary Village Mall, where he found his wife’s car parked in the parking lot. A quick check of the stores revealed no sign of Sandra, however, and none of the patrons or employees recalled seeing her that day.

Worried that something had happened, Robert called the police and attempted to report his wife missing. He was told that he needed to wait until she had been missing for at least 24 hours before he could file a missing person report. Frustrated, Robert searched around the area on his own before returning home with his daughter. He spent a nervous night waiting by the phone, hoping Sandra would call.

Robert called the police again early Monday afternoon and Sandra was officially listed as a missing person. Deputies from the Wake County Sheriff’s Office assisted Cary police officers in searching the area around the Cary Village Mall, but they found no clues to Sandra’s whereabouts. There was no sign of a struggle in or around her car, and they were unable to find any witnesses who remembered seeing Sandra park or get out of the vehicle.

Sandra, a nurse who was the supervisor of the blood bank at Rex Hospital, wasn’t the type of person anyone expected to disappear voluntarily. Robert told investigators that he initially thought she had some sort of car trouble that prevented her from coming home, but once he found the Chevelle he realized this wasn’t the case. He worried that the fact that deputies insisted on waiting 24 hours before taking a missing person report had hindered the investigation.

Wake County Detective Lt. S.M. Pickett defended the practice of waiting before launching a missing person investigation, pointing out that most adults return on their own within the first 24 hours. When Sandra didn’t return within that time period, four deputies were assigned to work on her case full-time.

Detective Lt. Pickett admitted that they didn’t have a lot to go on; the Chevelle had been processed for fingerprints but they didn’t find any clues to Sandra’s whereabouts. There were no unidentified fingerprints in the car and no receipts to show that Sandra had purchased anything before she went missing. “We’re looking for that one thing to show us what direction to go in. It’s extremely frustrating. We don’t have any evidence whatsoever of foul play, but as a missing person case lingers on longer, it causes the investigators to become more suspicious.”

Robert had suspected foul play from the beginning. He noted that Sandra was the type of person who always called home if she was going to be late; it was unheard of for her to disappear for any length of time. He was certain that someone was holding Sandra against her will. All he could do was pray that she was still alive and would soon be reunited with him and their daughter.

Detectives noted that most people who go voluntarily missing do so because of problems at home or work, but Sandra didn’t appear to have any reason to disappear. They found nothing to indicate she and Robert had any problems in their marriage and they were in good financial shape. Investigators had interviewed more than 100 people who knew Sandra, and all of them agreed that she simply wasn’t the type to abandon her family or her job. She was described as a wonderful wife, mother, and employee.

Robert, who worked as a financial aid officer at Central Carolina Technical Institute in Sanford, North Carolina, took time off so he could assist in the search for his wife. Five days after she was last seen, he admitted that it was getting harder to stay positive. “It’s very difficult. It’s been a lot of sleepless nights, and I walk the floor a lot. I have no real desire to do anything.” He kept busy distributing missing person flyers. “If there’s something I can do to help find my wife, I need to be doing that. I just couldn’t think about work.”

A week after Sandra disappeared, the Wake County Sheriff’s Office and the Cary Police Department set up roadblocks at each of the seven entrances to the Cary Village Mall. For four hours, they stopped each person entering the mall parking lot and asked if they had been there the previous week. They were hoping to find someone who had seen Sandra or witnessed anything unusual that might provide a clue to what happened to her. They spoke to nearly 800 people but none of them were able to assist in the investigation.

Detective Lt. Pickett told reporters that investigators had been baffled by the complete lack of clues in the case. “I wouldn’t say we’re leaning toward kidnapping at this point…we’re investigating all aspects of the case.” On January 16, 1984, investigators spent several hours flying over the Cary area in a helicopter, hoping to spot some clue to Sandra’s whereabouts, but didn’t find anything significant.

Wake County Sheriff John Baker said his detectives were stymied by the lack of information. “We don’t know anything more than we did the first day she was missing. We’ve found nothing helpful at all.” Although they hadn’t found any evidence of foul play, investigators considered Sandra’s disappearance to be suspicious; they didn’t believe she had voluntarily walked away from her life.

As the investigation entered its third week, Sandra’s friends and family members announced that they were collecting money to offer a reward. Robert said more than $4,000 had already been raised. “Maybe there’s somebody, just anybody, who thought they saw something, and now maybe they’ll tell.”

Frustrated by the lack of progress in the investigation, detectives with the Wake County Sheriff’s Office said that they were considering consulting with a psychic. While Sheriff Baker said that he personally didn’t believe in psychics, Detective Lt. Pickett admitted that they didn’t have anything to lose. “They may give us nothing, but that’s exactly what we’ve got right now — nothing.” Despite several searches and hundreds of interviews, investigators had been unable to uncover any useful information.

By the beginning of February, the reward for information in Sandra’s case was up to $10,000, but the case was beginning to stall. There had been no confirmed sightings of Sandra since she left her home to go to the pharmacy, and detectives admitted that they had no idea if she had ever made it to the shopping center or if someone had driven her car there and abandoned it.

A month after Sandra vanished, Wake County Detective Capt. T.W. Lanier told reporters there were no new leads in the case. He then quickly corrected himself, noting, “Actually, that may be misleading because I don’t know that we’ve ever had any leads in this case. We are still talking to people, but nothing at all has been developed.”

On March 2, 1984, a woman was driving in Cary when she was assaulted by a man who jumped into her car when she was stopped at a traffic light. He threatened her with a knife, forced her to move into the passenger seat, then drove her car to a rural area west of Cary. There, he and another man, who had followed in another vehicle, sexually assaulted the woman and then fled. The woman went straight to police. The following day, another woman was approached by a man with a knife when she was walking to her car at a different Cary shopping center. She managed to escape unharmed. Detectives weren’t sure if these cases were related to Sandra’s disappearance but said they couldn’t rule out the possibility. Sketches of the two suspects were released to the public but they were never identified.

Months turned into years, and Sandra’s case went cold. Robert continued to publish classified ads to advertise the $10,000 reward available for information, but all he received were crank calls. A year later, he withdrew the reward offer. Several years after his wife vanished, Robert moved to Greensboro. He told reporters, “There’s a point in time after five years or so where you just have to go on.” Much of his time was spent with his daughter, but he eventually started to date again and got remarried in 1991.

Sandra’s mother, Lucille Randall, continued to hope that her daughter would be found. In 1998, she said she remembered something significant that happened in the days leading up to Sandra’s disappearance but didn’t want to discuss it in detail. “It was something in her life. She did tell me a little something the last time I saw her.”

Lucille admitted that Sandra was always on her mind. “I can’t help but think of her every day, and I hope and pray that the good Lord will let us know something or find her or whatever.”

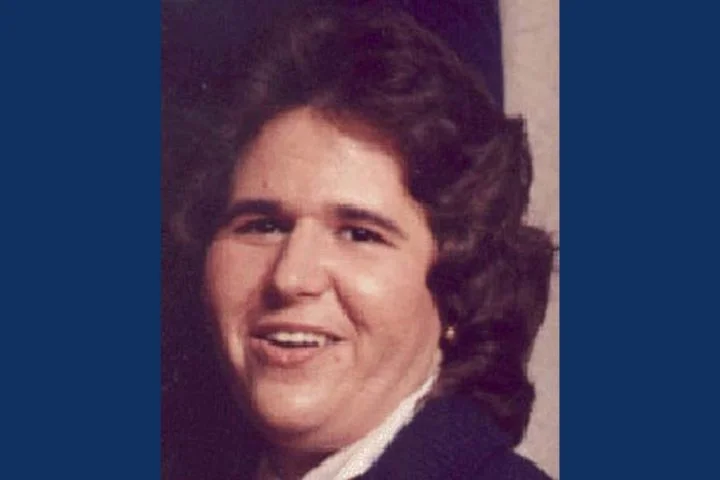

Sandra Kay Randall Ross was 31 years old when she went missing from Apex, North Carolina in January 1984. Detectives were never able to find any clues to Sandra’s whereabouts, but they do not believe that she willingly abandoned her husband and young daughter. Sandra has brown eyes and brown hair, and at the time of her disappearance, she was 5 feet 4 inches tall and weighed 120 pounds. Sandra was last seen wearing tan corduroy pants and a burgundy sweater; she was carrying a wine-colored purse. If you have any information about Sandra’s disappearance, please contact the Wake County Sheriff’s Office at 919–856–6800.