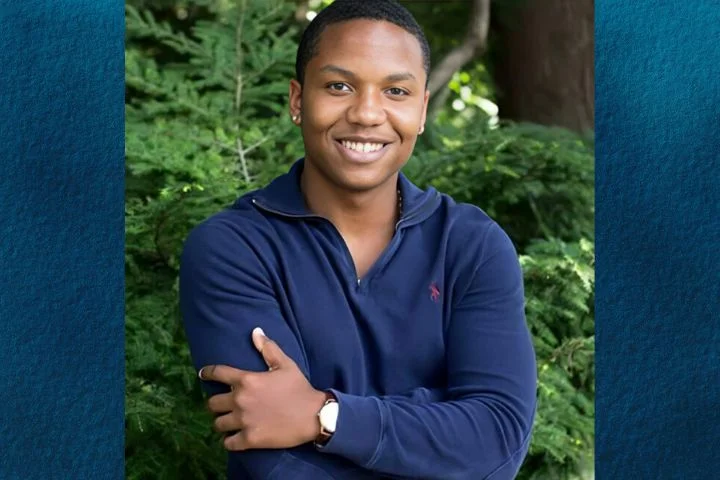

In the Grand Hall of the Neal Marshall Black Culture Center, a crowd listened as Vivianne Smedley recalled the events of Sept 28, 2015. She had received an early morning text from her brother. It read, “I’m leaving the country … Don’t try to contact me … I’ll contact you once I’m set up overseas.” Vivianne reported this to IUPD, and Joseph Smedley was announced missing.

The response of IU was far from appropriate. Despite sending out student alerts throughout that week pertaining to gas line breaks, not one alerted the campus a student was missing until that Friday, Oct 2, 2015, a few hours before Smedley’s body was found by a fisherman in Griffy Lake. A backpack full of rocks strapped to his body.

We shouldn’t pretend that IU doesn’t have a history of sensationalizing murdered or missing white students. Andrea Sterling, president of the Black Graduate Student Association, described the response to Joseph’s death on campus as living in “two worlds … this great population of students who had high anxiety levels and weren’t sure if they should be grieving or what, and some students who seemed like they had no idea what was going on.”

To Sterling, the message from both the University and local police was obvious; if you are a black student and your life is endangered, expect no response from the University. When a member of the crowd at the vigil asked Vivianne Smedley what the University had said or provided to her, she replied that the administration had sent her “a card.”

In the days following the discovery of Joseph’s body, it was revealed that a note had been found at Joseph’s off-campus residence. The note contained a message similar to the text received by Vivianne, except it was signed “Smedley,” and dated “9/28,” the day Joseph went missing. Despite a noticeable amount of unexplained circumstances surrounding Joseph’s death, on Dec. 4, Monroe County Coroner Nicole Meyer ruled the cause of death a suicide.

A second independent autopsy found hemorrhages on Joseph’s back that could be consistent with someone pressing down on him while he drowned.

This Forensic Pathologist was denied any access to the first autopsy and other records, with BPD citing Indiana Law and SOPs requiring them to go through the deceased’s “next of kin.” Since the body was found, police had opted to communicate with Vivianne’s estranged father, who Joseph had been legally emancipated from prior to attending IU. Even though Vivianne has been granted legal rights to Joseph by their mother, all of Vivianne’s attempts to get clarification from the police have been ignored.

When I asked Vivianne if she thought those that knew Joseph and had seen him last had been fully investigated by the police, she simply replied, “They were questioned, not interrogated. Those are two different things.”

Even the most incredulous of skeptics has to admit that when considering this litany of inconsistencies, the notion after a night of hanging out with friends, Joseph Smedley lied to his sister about leaving the country, then walked out to Griffy Lake, filled a backpack with rocks and drowned himself is at best a rickety narrative.

“Whoever knows should come forward,” Vivanne said. “I want answers. I want justice. I want his name in public.”