The last time anyone saw Bonnie Bickwit and Mitchel Weiser, they were standing alongside a highway in Narrowsburg, New York, attempting to hitchhike to Watkins Glen, 75 miles away. It was Friday, July 27, 1973, and the teenage couple wanted to attend the Watkins Glen Summer Jam, a large concert featuring the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers, and the Band. Mitch and Bonnie were among more than 600,000 people heading for Watkins Glen that weekend, but no one knows if they made it there or not. They were never seen again, sparking a search effort that is still going on nearly 50 years later.

Mitch, who was 16 years old, left his home in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, on Thursday afternoon. He had originally planned to attend the concert with one of his friends, Larry Marion. Although Larry’s mother was usually very lenient with him, she decided at the last minute that she wasn’t comfortable with him making the trip to Watkins Glen and refused to allow him to go.

Mitch had already taken time off from his internship with a photography studio on Coney Island and wasn’t willing to miss the concert. He decided to give Larry’s ticket to 15-year-old Bonnie, his girlfriend of about a year.

Bonnie had been spending her summer working at Camp Wel-Met in the Catskill Mountains. She had attended the camp for years as a camper and loved it but wasn’t very happy working there. She had been hired as a mother’s helper but believed her employer was taking advantage of her; she complained that she was sometimes made to work up to 16 hours a day and felt exploited. She jumped at the chance to see her boyfriend and go to Summer Jam.

Mitch’s mother, Shirley, hadn’t been thrilled about him going to Watkins Glen, especially once she learned that Larry’s mother wasn’t allowing him to go. She and Mitch’s sister, Susan, both tried to persuade the teenager to stay home, but Mitch was resolute. As he headed out the door, Shirley told him to wait for a minute and she would give him extra money to make sure he had enough to get there and back safely. If Mitch heard her, he ignored her. With just $25 in his pocket, Mitch left to meet Bonnie at Camp Wel-Met, nearly three hours away.

Mitch took a bus to Narrowsburg, the town closest to Camp Wel-Met. From there, he took a cab to the campgrounds, arriving shortly before midnight on Thursday night. By the time he arrived at the camp, he had already spent almost all of the money he had with him. When he called home to let his family know that he had made it safely to Camp Wel-Met, his sister was concerned to hear that he was almost out of money. She begged him not to go to the concert since he was essentially broke, but Mitch told her he would be fine and said he would see her on Sunday.

Bonnie had asked her employer for time off so she could attend the concert but he had refused; angry about the situation, Bonnie quit on the spot. There was no way she was going to miss out on going to Watkins Glen; she told her boss that she would be back by Monday to pick up her final check and her belongings.

Mitch and Bonnie spent the night at Camp Wel-Met and had breakfast in the dining hall on Friday morning before setting out on their journey. It was easy enough to get a ride into the town of Narrowsburg — a large number of trucks and vans entered and left the camp during the day — so the pair simply stood along the road running through the campground and waved at passing vehicles until one of them stopped.

A man driving a truck picked up the couple and drove them into Narrowsburg. They politely thanked him for the ride as they climbed out of his truck and headed for the side of Highway 97, holding a cardboard sign Bonnie had made the night before with their intended destination written on it. As the truck driver pulled away, he caught a final glimpse of the teenagers, standing alongside the road with their Watkins Glen sign. It would be the last verified sighting of the pair.

Mitch’s parents were the first to realize that something was wrong when he hadn’t returned home by Sunday night. By Monday morning, they were starting to panic. Shirley called Camp Wel-Met, hoping that Mitch was just spending extra time with Bonnie, but learned that Bonnie had never made it back to camp. Fearing the worst, Mitch’s father, Sidney, decided to drive to Watkins Glen to look for his son. Susan went with him, while Shirley stayed at home by the phone, hoping to get a call from Mitch.

Bonnie’s parents, Theodore and Rae, were on vacation in Cape Cod at the time. They had no idea that Bonnie had planned on going to the Summer Jam concert, let alone that she was missing. They learned of her disappearance that Tuesday when they returned to their home in Brooklyn’s Borough Park neighborhood. Someone from the camp called looking for Bonnie, then explained that she had gone away for the weekend and not come back. Her parents were horrified.

Ted and Rae immediately got into their car and drove to Camp Wel-Met. From there, they reported Bonnie’s disappearance to local authorities. They expected police to help them find their missing daughter, but law enforcement brushed off their concerns. Bonnie was 15 years old and had quit her job to go to a concert; in the eyes of police, she was just another teenager who had gone voluntarily missing and they weren’t going to waste their time looking for her.

Just three days before she went missing, Bonnie had mailed her parents a letter. In it, she spoke of how much she was enjoying the freedom she had at Camp Wel-Met and hoped that her parents would give her this same freedom when she returned home at the end of the season. She spoke of wanting to travel, giving her parents hope that she was doing just that. They tried to tell themselves that she was fine, simply trying to assert her independence, and would be back before school started in the fall.

Both sets of parents waited anxiously as the start of the new school year approached. When the first day of classes came and went without any sign of Bonnie or Mitch, their parents feared that something horrible had happened to them.

Mitch and Bonnie had met at John Dewey High School in Brooklyn, an alternative school for gifted students. Both of them were highly intelligent honor students who had big plans for their futures, and no one thought that they would have willingly given up on these dreams. Friends pointed out that Mitch had been scheduled to complete his coursework and graduate in January; he had already made plans to attend Brooklyn University.

It had been more than six weeks since anyone had heard from either teenager, but law enforcement still refused to take their disappearances seriously. The Bickwits and the Weisers were forced to launch their own investigation into what had happened to the pair, and they did everything they could think of to publicize the case. They wrote hundreds of letters to police departments and newspapers around the country and mailed out thousands of missing person flyers, all to no avail.

Classmates at John Dewey High School were determined to help in the search for their missing friends. That winter, they held a “Have-a-Heart” sale around Valentine’s Day, selling candy, caramel apples, T-shirts, and other holiday items, hoping to raise money to help look for Bonnie and Mitch. Between sales and donations, they were able to collect $650, which the Bickwits and Weisers used to hire a private investigator. Unfortunately, not even the private detective was able to locate the couple.

There were several theories about what might have happened to Bonnie and Mitch, but little evidence to back up any of them. At first, classmates whispered that the pair had likely decided to elope; unbeknownst to their parents, the teenagers had secretly exchanged wedding rings that summer but there was nothing to suggest that they made it official.

Officials with the Sullivan County Sheriff’s Department, who were technically in charge of the case, believed that the two had simply run away. They pointed out that Bonnie had been unhappy with her job and had returned to her Borough Park home while her parents were on vacation and retrieved some money she had been saving. Police believed she had intended to use the cash to run away. Her parents, however, were doubtful. Bonnie only had about $80 in savings, hardly enough to finance a life on the run.

Mitch’s family also disagreed with the runaway theory. Mitch had been looking forward to getting his driver’s license and had a lesson scheduled for the Monday after the concert. He had also been excited about finishing high school and starting college. Although he had a bit of a rebellious streak, he was extremely smart and wouldn’t have done anything to jeopardize his future.

Both teenagers were intelligent and responsible; although neither family thought they were the type to get caught up with a religious cult, it was a possibility they couldn’t ignore. They wrote letters to different underground newspapers and even tried to infiltrate one or two cults in an effort to see if Bonnie or Mitch had been spirited away by one, but they never found any evidence of the missing teens.

Years went by, but the mystery of the missing couple remained unsolved. Mitch’s parents moved from New York to Arizona in 1984 but paid extra to make sure their Arizona phone number was listed in the New York City phone book. They wanted to make sure Mitch would be able to find them if he was still out there somewhere. Bonnie’s father, Ted, died in 1979, but her mother remained in the same Brooklyn Park home where Bonnie had grown up.

In 1987, Sidney Weiser was sitting in his Arizona home when the phone rang. When he answered, an operator told him he had a collect call from Bonnie and asked if he would accept the charges. He excitedly told the operator that he would, but after a few seconds of silence, the operator said that the other party had hung up. If it had been Bonnie, she never made any other attempts at contacting Mitch’s parents — or her own. It seems likely that the call was nothing more than a cruel prank.

By 1998, Bonnie and Mitch had been gone for 25 years and investigators finally decided to take a fresh look at the case. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which hadn’t existed when the teenagers disappeared, produced age-progression photos of the couple to show what they might look like at the age of 40. Posters were created and posted on various internet sites as well as across the country; some long-haul truckers even had pictures of the pair painted on the backs of their trucks to give the case some much-needed national exposure.

Philip Mahoney, who was a New York City Police Lieutenant in 1998, admitted that the case had been poorly handled from the start. No investigation had been done when the pair went missing and the original case files — which had included irreplaceable dental records for Bonnie and Mitch — had been lost. Mahoney was blunt with reporters, telling them, “It’s an embarrassment for us.”

The New York City Police Department had never been the primary investigative unit assigned to the case; they had only gotten involved because both Mitch and Bonnie lived in the city. Since the couple had last been seen in Narrowsburg, the case belonged to the Sullivan County Sheriff’s Department; unfortunately, their original case file had also been lost.

The families appealed to Eliot Spitzer, who was the New York State Attorney General in 2000; they wanted his office to get involved since the initial investigation had been completely botched. A representative from his office stated that they would touch base with the Sullivan County Sheriff’s Department and the New York City Police Department to check on the current status of the investigation before deciding if it was appropriate to involve the Attorney General. Unfortunately, dealing with the aftermath of the events of September 11, 2001, soon took precedence over the missing teenagers’ case.

Mitch and Bonnie’s disappearance was featured on an episode of the MSNBC television show “Missing Persons” in October 2000. After the episode aired, a handful of potential tips were called in to investigators. One of these, from a man named Alan Smith, was of particular interest to detectives and they traveled to Alan’s home in Providence, Rhode Island to interview him.

Alan claimed that he had attended the Watkins Glen Summer Jam and had hitched a ride home in an orange Volkswagen van. According to him, Mitch and Bonnie had hitched a ride in the same van on the day after the concert, which would have been Sunday. Alan couldn’t remember the name of the van’s driver but he did recall that the Volkswagen had a Pennsylvania license plate.

Alan told investigators that he and the driver had been stoned at the time, so his recollection of the day’s events was somewhat fuzzy. Along with Bonnie and Mitch, who had not been doing drugs and appeared to be sober, the driver of the van also picked up another man who was extremely stoned and spent the ride passed out in the back of the van.

At some point during their ride, they had decided to stop at either the Susquehanna River or the Chemung River to cool off. Bonnie had run into trouble while in the water and Mitch had attempted to save her, but both of them were pulled downriver by the current. Alan assumed they had drowned. Rather than attempt to get help for the teenagers, Alan claimed he and the driver had simply gotten back into the van and continued on their way.

Detectives initially thought Alan’s story was plausible and asked him to take a ride with them to see if he could identify the spot where they had stopped to swim. Alan was unable to pinpoint an exact location. Undeterred, the investigators began contacting each coroner’s office located along both of the rivers mentioned by Alan to see if any of them had a record of any unidentified bodies in the water. None of them did.

Investigators eventually determined that Alan wasn’t telling them the truth. He was unable to pick Bonnie or Mitch out of photo lineup or describe the clothing they were wearing. It was possible he had been so stoned that he had simply imagined such a scenario and then decided to insert Mitch and Bonnie into it after seeing their case on television.

In April 2001, several inmates in a Maryland prison contacted officials and claimed that another inmate had confessed to ki*lling Mitch and Bonnie. This inmate, who had been convicted of two mu*rders, was interviewed by detectives and admitted to k*illing the couple, but was unable to provide any accurate details. He claimed he had been in the New York area in 1973 and drew investigators a map of where the crime had supposedly taken place, but none of it made sense to detectives. They concluded that the man, who was already in jail for life, had just been boasting to other inmates and attempting to take credit for a crime he hadn’t committed.

The case went cold for another 15 years before a new lead surfaced. This one led investigators to a property near New York’s Keuka Lake, about 30 minutes away from Watkins Glen. Although detectives remained tight-lipped with the public, it appeared they had gotten a tip that Mitch and Bonnie’s bodies were buried somewhere on the property. They spent several days searching the property but found no signs of the missing teenagers.

In 2020, detectives searched a property in Bath, New York, after another tip came in about the possibility that Mitch and Bonnie might be found there. According to Sullivan County Undersheriff Eric Chaboty, “We jackhammered someone’s stairs. We had to replace them.” They found nothing to indicate the couple had been there.

The search for Bonnie and Mitch is ongoing. Although most people believe that they ran into foul play shortly after leaving Narrowsburg, others think it’s possible that they are still alive. To date, there has been no evidence found proving that the couple made it to Watkins Glen; Mitch’s best friend, Stuart, has spent hours combing through thousands of pictures taken at the Summer Jam concert but has never found any photos of Mitch or Bonnie. They may have run into foul play before ever making it to the concert they so dearly wanted to see.

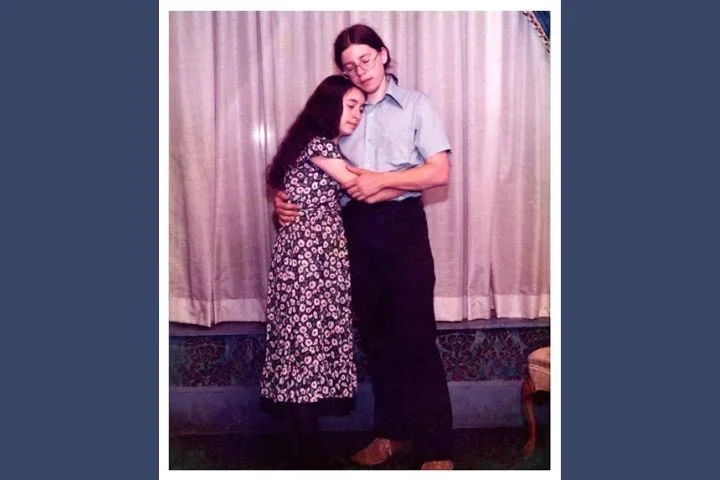

Bonita “Bonnie” Bickwit was 15 years old when she went missing in 1973. She was a highly intelligent young woman who loved to travel and had an extremely close relationship with her parents. She has brown hair and brown eyes, and at the time of her disappearance, she was 4 feet 11 inches tall and weighed 90 pounds.

Mitchel Weiser was 16 years old when he went missing with Bonnie in 1973. He was an intelligent and responsible young man who was preparing for his high school graduation and had already decided which college he was going to attend the following year. He has brown hair and hazel eyes, and at the time of his disappearance, he was 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighed 140 pounds.

If you have any information about Mitch or Bonnie — or any photographs from the 1973 Watkins Glen Summer Jam — please contact the Sullivan County Sheriff’s Department at 914–794–7100.