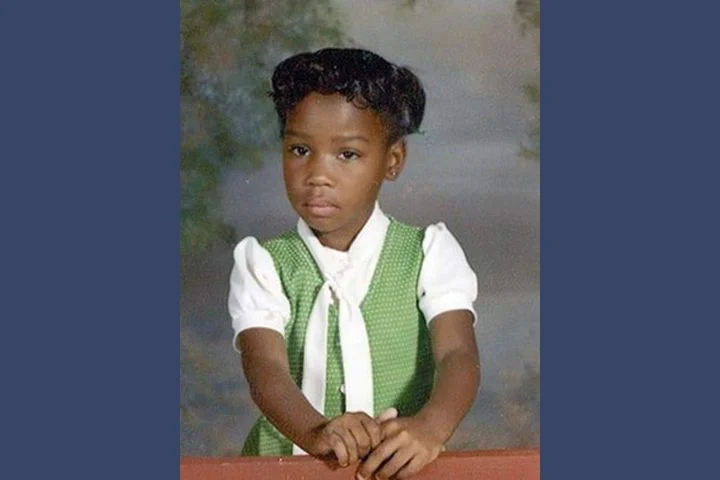

She walked out the door the day after Christmas 1980 with her hair in ribbons and 58 cents in her pocket to buy her mother a Coke.

The ribbons had faded by the time police found her more than a year later, buried under a cattle chute with a wire wrapped around her broken neck.

Avery Vernie “Peaches” Shorts would have turned 36 years old last week. She never made it past her sixth birthday, never made it home from the store – maybe never lived past sundown that day.

“Look how long it’s been, and still nobody’s come forward,” said her mother, Hazel Smith. “I just want to know, why did it happen?”

Knoxville Police Department investigators settled on a single suspect within a day of the girl’s disappearance. He smiled and laughed through every interrogation.

He never cracked, never confessed – never gave a team of detectives the break they needed to make their case.

“We tried so hard to get justice for that little girl,” said Jim Winston, a retired KPD lieutenant who led the investigation for years. “For all practical purposes, we were able to solve the case. We just weren’t able to put him away.”

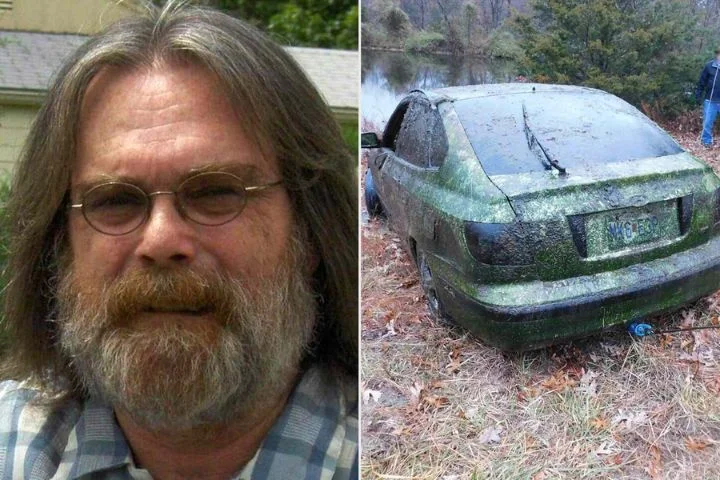

That man lies in a nursing home bed today, his body shriveled by age and his mind clouded by dementia. He denied the crime then. He denies it now.

“It wasn’t me,” he said. “I never killed anybody in my life – man, woman or child.”

Police thought Mitchell Arvell Reed – or Mitchell Arvell Webb, as he’s sometimes known – died years ago. They reopened the case this month after the News Sentinel tracked him down.

“We’re going to take one more shot at it,” said KPD Lt. Doug Stiles, commander of the Violent Crimes Unit. “It’s not over until we bring it to some type of resolution.”

Detectives hadn’t questioned Reed about the case in more than 20 years – until Friday night, when KPD investigators Ryan Flores and Lynn Clemons paid him a visit.

“He didn’t have much to say,” Stiles said. “He recalled it fairly well. He’s changed his story on some things, but he’s still adamant he was not involved. He told us we’re barking up the wrong tree.”

Investigators hope to rebuild the case file in the days to come.

“We’re recovering stuff from storage, and we’re trying to make sure we have all the physical evidence together,” Stiles said. “We’re not at a dead end.”

Reed says he’s not worried. Any threat of arrest, trial or prison means little now.

“They used to say he’d die an old man in jail,” said his wife, Mary. “But he’ll die an old man in a nursing home.”

A trip to the store

Christmas had come and gone, and Hazel Smith was thirsty. The 22-year-old divorced mother of three had smoked her last cigarette and was getting ready to cook supper.

So she sent her 6-year-old daughter, Peaches, to the store for a Coke. The weather was cold outside, almost freezing, and Smith made sure Peaches buttoned up her coat and laced up her Mickey Mouse tennis shoes before heading out the door around 3:30 p.m.

“She was my oldest, and she was my pride,” the mother said. “When she was born, she had such a round little face she looked just like a little peach.”

Smith still lives in the Montgomery Village housing project in South Knoxville, just around the corner from the apartment on Joe Lewis Road where she heard her daughter’s voice for the last time.

“As she went out the door, she said, ‘Mama, I love you,’ ” the mother recalled. “I think about that every day. Every time I go past there, I look, and it hurts.”

Mitch Reed stopped by the apartment just before Peaches left. He asked Smith – again – to let him move in with her.

Reed was 47, slight and balding. He split his time between his parents’ home in Rockford and girlfriends’ apartments in Montgomery Village. He’d met Smith that summer, bought her clothes and a camera, and driven her and the children around in his brown Cadillac.

Smith asked him for money for a Coke and said she needed time to think. Reed knew she’d spent the night before with another man. He didn’t like her answer – not any better than months earlier, when she told him she’d lost the clothes and the camera.

“Something just told me he couldn’t be trusted,” she said. “He’d asked me to be his old lady before, and I’d told him no. That’s when he made the remark that he’d get even.”

Reed dumped 58 cents on the counter and stomped out. Peaches left for the store.

The walk to the store on the corner of Maryville Pike took about 15 minutes round-trip. Peaches stopped to play but got to the store by 5 p.m. Her mother called police about 50 minutes later.

“It never took her that long to get to the store,” Smith said. “I asked them at the store, and they’d said she’d already been there. I knew she wouldn’t have wandered off, and I knew she wouldn’t have got in a car with a stranger.”

A search through the snow

Officers organized volunteers for a search. They retraced Peaches’ steps, swept the woods, walked the nearby railroad tracks and knocked on every door in the project.

The search stretched past midnight and grew to include more than 100 volunteers. KPD Lt. Jim Winston learned of the search when he saw it on the television news.

Police didn’t assign a detective until the next day. Winston said that time lag still bothers him.

“It was going on 24 to 36 hours old by the time we got involved,” he said. “I feel like it might have made a difference if we’d been able to get on it sooner.”

Deputies, rescue squad members and dogs joined the effort. Police Chief Bob Marshall assigned a 12-man task force, headed by Winston, to bring Peaches home.

Parents hugged their children a little tighter as the news spread across East Tennessee and the country. The headlines joined reports of the Atlanta child m*urders, then still unsolved, and later the mur*der of Adam Walsh as a nationwide panic set in over abductions by strangers.

Searchers worked around the clock and into the new year. Snow fell as temperatures dropped below 0. Spirits fell, too.

“We knew we would have a body eventually, but we didn’t know where,” Winston said.

Winter turned into spring. Christmas and another New Year’s Day passed.

They couldn’t get nothing on me. That’s why I gave them a hard time. A cop might say anything to get you to talk. If they say I did it, let them try me.

Then on Jan. 23, 1982, a father and son hunting rabbits walked up on a skull near a dump on the University of Tennessee Extension Farm off Singleton Station Road in Blount County. A pair of Mickey Mouse shoes lay nearby, next to an overturned cattle chute.

KPD Investigator Randy York, now retired, remembers what lay beneath.

“We pushed up on it, and sure enough, there lay her little body with that wire wrapped around her neck,” York said. “Her pigtails were there where her head would have been, and her hair still had the ribbons in it. She still had her panties on and a little coat buttoned all the way to the top.”

Forensic anthropologist Bill Bass identified the bones as Peaches’. Her parents buried her six days later in a donated grave.

A familiar face

Finding Peaches’ body gave the case new life. Police already had interviewed more than 100 people, but they kept coming back to one man – Mitch Reed.

The body lay about a 15-minute drive from Montgomery Village and within about a mile of the house in Rockford where Reed’s parents lived. Its condition offered little to work with – a decomposed skeleton and a rusty 9-gauge wire.

The wire came from the UT farm, a brand made in the 1940s. Winston believes Peaches’ k*iller stra*ngled her by hand in a car, then drove to the farm and coiled the wire around her throat to make sure she was dead.

The wire yielded no fingerprints. Any blood had dried up long ago. Winston doubts even modern forensics could do much more with evidence exposed for so long.

Police knew Reed’s name long before Peaches disappeared. He’d spent much of his life in and out of jail for thefts and burglaries – all the way back to age 15. Officers had questioned him just a year before in another de*ath, the str*angling of 62-year-old Emma Brewer in her Western Avenue apartment, but never filed charges.

Reed didn’t mind talking to detectives.

“He enjoyed being the center of attention,” Winston said. “He was such a rat – always smoking, always grinning. Life was just a big con game to him. You could tell by the gleam in his eye. He would talk with us for hours about his life, his job, his criminal record. But he never would admit to hurting a child.”

A dog found Peaches’ scent in the Cadillac – the one Reed used to give Smith and her children a ride. Reed admitted he’d been to the store, just after his argument with Peaches’ mother. He said he drank a cup of coffee outside and never saw Peaches.

He refused a polygraph, the same as he’d refused one in the Emma Brewer case.

“He said he just didn’t believe in being hooked up to machines,” said KPD Sgt. Ray Perry, now retired. “He told us, ‘If I was laying in the hospital dying, I wouldn’t let them hook no machine to me.’ “

Once Winston thought he had his break. A boy told police he’d seen Peaches outside the store, talking to a man who looked like Reed with a brown car.

“We almost had enough, but he recanted,” Winston said. “He was just a kid, and we always thought his parents might have pressured him to change his story.”

A fading memory

Knoxville police never made an arrest in Peaches Shorts’ d*eath. The department took Jim Winston off the case later that year.

Mitch Reed went to jail again in 1983 for burglary of a rental shop. A 1985 conviction sent him to pr*ison for the next decade and a half. He last faced a judge in 2002, when he pleaded guilty to misdemeanor as*sault on a child.

Reed spends his days now in bed or a wheelchair at the NHC Healthcare of Fort Sanders nursing home, sometimes on a breathing machine. He can barely stand on his own, sometimes barely wrap his fingers around a cigarette.

He jokes with the nurses and waits for visits from his wife. He can’t remember his age – 77. He can’t remember his birthday.

But he remembers a name – Peaches.

“I knew Peaches,” he said. “I can’t say I didn’t, ’cause I did. What happened to her?”

Emma Brewer’s name gets no reaction, at least not at first.

“I’ve been there,” he said. “I’ve been in that house, but I ain’t ki*lled nobody.”

Mention Winston’s name, and the memories start coming back.

“They couldn’t get nothing on me,” he said. “That’s why I gave them a hard time. A cop might say anything to get you to talk. If they say I did it, let them try me.”

His wife, Mary, remembers Peaches, too. She lived just around the corner from the girl. Reed often stayed with her there.

She talked to police then and passed a polygraph. Ask about her husband today, and she hesitates.

“I won’t say he didn’t do it,” she said. “He never talked to me about it. If he did it, he knows.

“God knows who did it. God knows, and he knows.”

Matt Lakin may be reached at 865-342-6306.